How The Orphanage Fine-Tuned Frank Miller's Color Workflow

Not Easy Being Green

The Spirit was shot digitally – a logical choice given the large number of VFX-with the Panavision Genesis by cinematographer Bill Pope, ASC. Maschwitz’s first idea was to use color-correction on set to tone down the omnipresent green screen, suppressing it to gray, black or white. “There’s something that happens when you see green,” said Maschwitz. “It’s horrible when you’re trying to create an image, and I wanted Bill to light a scene the way he wanted to light it.”

In addition to using color-correction as a production tool, Maschwitz brought the DI to the set to do as much color-correction as possible in production via the use of LUTs. The work to create an agreed-upon LUT took place during a pre-production test period, when the HDCAM SR tape was transferred to 10-bit DPX files. Using test footage, cinematographer Pope, with Maschwitz and DI artist Aaron Rhodes, color-corrected in After Effects up until the first day of shooting. Pope was then able to apply the LUTs non-destructively to the footage on-set. “I built color-corrections not just to be a creative representation of what Frank was interested in, but also to accurately reflect how the movie would look on film in a theater,” said Maschwitz, who noted that later versions of After Effects allowed them to emulate the look of Kodak film stocks. “The result was that on-set we saw gorgeous, stylized Frank Miller drawings come to life on an HD monitor. It didn’t require levels of abstraction.”

Creating these LUTs in advance with Pope and Miller also gave everyone the confidence that the filmmaker’s vision would prevail throughout the digital production and post. “I didn’t want anyone to think that I thought it was raw material I could play with,” said Maschwitz. “I was reverential with Bill’s footage and Frank’s direction. The idea was not to turn this into a big three-month visual-effects shoot. It should be a creative shoot, not a technical one. I geeked out obsessively about setting everything up, to let people be creative.”

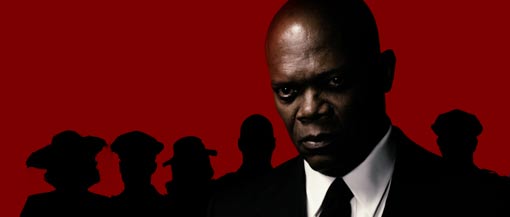

The LUT, which was fine-tuned multiple times before the shoot, was dubbed Masch 4 (Masch 1 through 3 were “beta” versions). “That shows how in sync we were, that we didn’t go through 100 versions,” said Maschwitz. The LUT was useful for many of the film’s stylized sequences. For example, it enabled them to turn the images into silhouette. “We used that for those shots where the Spirit is a silhouette and only his tie pops out,” he said. “On the set, we had ultra-violet light projected onto the tie. Everything green-screen went white, everything else went black – except everything red, like the Spirit’s tie, went more red.”

VFX producer Nancy St. John saw first-hand the impact of the on-set color-correction. “This was key to opening up the feel and look of the film to everyone on set,” she said. “Everyone was able to see on the monitors something that looked very similar to the finished product. This helped foster the willing suspension of disbelief, allowing everyone to concentrate on the craft of filmmaking, not the green screen. This previsualized look also went into the cutting room, allowing the editing process to be green-free as well.”

A LUT You Can Live With

With a LUT everyone agreed on, DI artist Rhodes worked on the digital intermediate every day throughout the production, as the footage flowed in, using a Digital Vision Film Master. By the time the production wrapped, 90 percent of the DI was done, with the final polishing phase completed at post-production house Modern VideoFilm. “Aaron [Rhodes] had a great continuity with the movie,” said Maschwitz. “It’s amazing to have a colorist who’s spent three months with the cinematographer as opposed to meeting him for the first time after production. This nets out to better creative decisions and also efficiencies, which is important when there are 2,000 shots.”

Those effects were created at 10 VFX companies in four countries (U.S., Canada, Australia and Mexico). In addition to The Orphanage, the VFX facilities were Digital Dimension (376 shots); Fuel FX (310 shots); Riot (235 shots); Entity FX (170 shots); Look Effects (62 shots); Furious FX (75 shots); Rising Sun Pictures (73 shots); Ollin Studio (37 shots) and Cinesoup (54 shots).

Maschwitz sent each VFX vendor a complete “color pipeline toolkit” that included the LUTs, sample frames, editorial and other information. “I sent them everything I’ve always dreamed of getting as a VFX house,” he said. “We were really trying to turn this into an experience where every bit of time could be expended creatively, rather than trying to get things to work.”

One of the key pieces of software that made the entire system work was cineSync, a software tool from Rising Sun Research (RSR) for remote collaboration and review. The disparate parties were able to watch the same QuickTime files and, more important, draw on the frames and scribble notes. “We turned it into full interactive concept art sessions happening live on the other side of the planet,” said Maschwitz. “At the end, cineSync saves all your drawings so it becomes direct reference.”

St. John agreed that the cineSync tool was invaluable. “It’s also a great tool to paint on, not merely to illustrate a specific issue within a shot, but to actually paint a new frame or several frames,” she said. “This is where Stu took this tool to new heights, as it allowed him to paint on a shot and create a look frame good enough for a vendor to take and imitate. He used the tool so well that sometimes vendors joked that they might just deliver back the look frame.” Maschwitz also noted that director Miller also got involved in hands-on painting.

The Orphanage team worked closely with RSR throughout the film to refine control of the paint tools. “This [use of cineSync] brought us that much closer to a finished concept and advanced the speed of our production greatly,” said St. John. “The ability to communicate with clients and vendors efficiently and in a manner that was verbally and visually comprehensible was paramount.”

The vendors sent dailies, as QuickTimes, with the LUT burned in. “When they sent the final shots, they would secure-FTP us DPX files that didn’t have the LUT baked in,” Maschwitz said. “Then we applied the LUT in the Digital Vision Film Master and everything matched.”

VFX in Review

The entire film was loaded into The Orphanage’s system three times: the raw plate and at least two iterations of every shot, representing the most recent versions of VFX submitted by a vendor. “That way we could easily see the changes made when the new iteration was submitted,” said St. John. “We not only could do the classic A/B process, switching between the two takes and/or the plate, but it also allowed for a stealth viewing mode that would show a red overlay where the image was different and a slightly grayed out version of the image where it was the same. This viewing enabled us to see the subtlest of differences.”

For example, in a scene where the only thing altered between two takes was a wire that was removed, the majority of the shot would be grayed-out but still visible, with a bright red line where the wire had been removed. “This greatly expedited the technical review process,” said St. John. “We didn’t have to guess what was different, a strategy that could lend itself to human error.”

Though the VFX facilities were in locales around the world, the dailies process became an intimate environment. “Some of these VFX facilities only know each other through the cineSync sessions,” said Maschwitz. “But it was enough and it felt very personal.”

For More Info:

Panavision Genesis

Adobe After Effects

Rising Sun Research cineSync

Digital Vision Film Master

When the cut was locked and ready to be composited, The Orphanage team loaded the raw plates into the Digital Vision Film Master, applied the pre-vis look to the plates and to the comps as they came in. “It gave us ultimate control over the image,” said St. John. “We could dial to taste each shot’s look and then balance across shots and scenes.”

Maschwitz noted that various portions of the Spirit workflow had been used on past films, most recently John Woo’s Red Cliff and a handful of commercials. “It’s the perfect system for doing a movie like this that is so heavily dependent on its look and has so many visual effects,” said Maschwitz. “Having said that, it took a leap of faith for the director and producer to let us do the DI and control all this from our San Francisco facility.”

Next up for The Orphanage color pipeline is Legion, an Orphanage original production and the directorial debut of Orphanage senior staffer Scott Charles Stewart. “I’d be perfectly content to use this [color pipeline] for internal productions,” said Maschwitz. “But I think we’ve already shown it to directors and VFX supervisors who think this is the way it should be. The way a movie looks is increasingly influenced by the digital color-correction and the visual effects. And I think that’s true for all movies at every budget level.”

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.

Leave a Reply