Eque on Repairing the Negative, Fixing the Color, and Cleaning it All by Hand

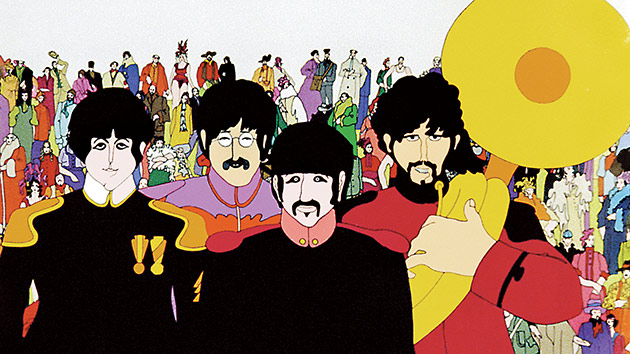

In The Beatles' 1968 animated classic Yellow Submarine, George Harrison declares, "It's all in the mind." But dirt, tears and scratches on the iconic film's original camera negative were all too real. So discovered restoration supervisor Paul Rutan, Jr. and his team at Eque (formerly Triage Motion Picture Services) in Los Angeles when restoring the film for its recent Blu-ray, DVD and iTunes releases for The Beatles’ Apple Corps Ltd. and distributor Capitol Records. Though the movie had been reissued on DVD and VHS in 1999, a thorough restoration had never taken place. Rutan had previously supervised the restorations of the group’s A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and Help! (1965), but this reissue presents the first-ever official Blu-ray product from the Beatles canon.

Hollywood-based Eque (pronounced “E-Q”) did a combination of photochemical and digital restoration on Yellow Submarine. “I describe it as restoring the photochemical elements and remastering the digital elements,” Rutan says.

All images © Subafilms Ltd.

Back to the Start

The team started with the original five-reel U.S. camera negative, stored at Pro-Tek Vaults in the San Fernando Valley. The neg, filmed as a full 4:3 frame, though shot for 1.66:1 aspect ratio, first received a thorough cleaning and inspection. “We repaired 40-year-old splices that were falling apart and cemented any tears. But we also noted locations of any damage that we knew the wet-gate printer wouldn’t be able to remove.”

In a standard dry-gate contact printer, scratches in the negative can become even more visible due to refraction of light as it passes through the scratch surface. In a wet gate printer – Eque has five – the negative and raw stock are run through liquid perchloroethylene, which momentarily fills the scratch as it passes through the gate, acting as a continuous base material with little or no refraction. “It’s almost 100% effective as long as the scratch doesn’t cut through the top layer of the emulsion,” Rutan explains.

After the physical repairs were made, an interpositive was struck, which was then scanned at 4K through Pixel Perception’s (a sister company to Eque) archival scanner, built by Chris Duscendschön. The one-of-a-kind scanner features Oxberry movements and equipment, with the ability to scan film formats from 8mm to VistaVision at resolutions from HD to 4K. The scanner can also print extremely shrunken film, all with wet-gate technology. Although Eque scans this type of material daily, this approach is actually discouraged by Rutan, who is an accomplished archivist, as well as a veteran film technician.

Notes Duscendschön, “We always strive to do a photochemical preservation first, to protect the original materials and to create a better element (in this case a timed wet-gate interpositive) for scanning.”

Prepping the Film Elements

A wet-gate timed first trial print was made from the negative, after which color-grader Sharol Olson, a 12-year veteran of the company, made timing corrections on a Hazeltine Color Analyzer. “Paul and I screen the print together and decide [on] the color palette that we want to go with,” Olson explains.

“We had no guide for the color,” Rutan adds. “I actually went to Amoeba Records and paid $40 for one of the out-of-print 1999 DVDs! But we just looked at that to see what had been done before. It was ugly. The bottom line was to simply do the best job we could, to our trained eyes and to what the original negative was trying to communicate to us.” Even with colors of elements of characters changing from scene to scene — and sometimes from shot to shot — the color now appears equal, balanced and smooth between cut-backs, Olson notes.

Olson applied her corrections, and eventually a final answer print was struck that satisfied both Olson and Rutan’s idea of how Yellow Submarine should look. That print was then sent off to Apple in England for approval.

A new interpositive was then made from the original negative, using the wet-gate printer and Olson’s approved color corrections. That interpos was then scanned on the Pixel Perception Archival Scanner at 4K, to become the basis for the restoration, known as a raw scan.

Cleaning Up the Digital Picture

Because photochemical materials are incompatible in the digital world, digital colorist Randy Walker then went to work in Eque’s Hollywood Digital Suite, using a Nucoda Film Master digital work station. “The Film Master is an excellent tool for both post-production and restoration,” says Rutan. Walker first applied a base color-correction to the film, which was then sent, scene by scene, to Eque’s studio in Hyderabad, India, where between 40 and 60 digital artists performed most clean-up tasks, using the same Nucoda tools Walker was using in Hollywood.

One thing they didn’t use was any automated digital restoration systems, such as Digital Video Noise Reduction (DVNR) or other proprietary dirt-removal tools. “Their specific instruction was to hand-clean everything – not to use any automated processes,” Walker explains. “Any time we tried to use automation, it would get a hold of fine detail in the black lines – eyes, eyebrows, outlines, pencil line detail – and ruin it. It actually does a very good job at identifying dust, dirt and scratches, but with animation, it goes after those black lines every time.” 130,000 frames were thus repaired, one at a time, over a period of about two months.

Walker also sent along JPG images with portions of frames circled to advise the Hyderabad team of any unusual areas which, at first glance, might appear to be damage or mistakes, but which were actually part of the artistic technique used in a particular sequence. “Paul wanted the image to still look like art from 1968,” he says. “I took care of anything egregious. Anything they couldn’t remove without creating artifacts they were instructed to send back so we would decide what to do with it.”

Upon return of the scenes to Hollywood, the high-quality work achieved overseas was evident. Says Rutan, “We had preserved pieces of the 1968 Interpositive, just in case we might need them for any severely-damaged scenes (as well as for Apple’s future use). But Team Eque did such a superb job doing repairs and cleanup, we didn’t need to use it at all. They’re an amazing group of artists.”

What's Art, and What's an Error?

The film contains a wide variety of what were, at the time, experimental animation techniques, including free-form, hand-drawn rotoscoping, watercolor, animation of still photos and even use of an array of Scotch tape to produce a kaleidoscopic effect, along with traditional cell animation. So tricky, then, was the matter of determining what items, if any, were true mistakes which needed to be corrected and which items might be mistakes, but were inherent in the original animation and needed to remain intact as part of the history of the film itself.

One of the movie’s original animation directors, Bob Balser, was called upon for guidance in some instances. In the “Eleanor Rigby” sequence, for example, created by effects animator Charlie Jenkins from still photos he’d taken of Liverpool, a dark clock tower was created by several cell layers – including live action footage of the setting sun, a silhouette of the tower and another of the clock face itself – which move about separately within the frame slightly. “Bob wanted us to fix that clock. It was something he’d always seen and wished he’d done over. But we couldn’t – it’s part of the film,” Rutan says. “But once he saw our final, improved result, he was perfectly satisfied.”

In another, the “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” sequence, with its unique hand-drawn rotoscoping and splotches of paint to create dancing characters, Rutan noticed a repeating smudge of paint outside the character lines – clearly a mistake. “It pops up three times. We ran that by Apple to ask if we could remove it, and, for something like that, they said, ‘By all means, take that out.’ Our rule of thumb was, if it didn’t flow with the action, then it probably didn’t belong.” Adds Walker, “That’s another example of where automation would have taken out all the brush strokes and ruined the highly stylized sequence.”

One More Thing …

Like the 1999 DVD, the new release includes the rarely-seen “Hey Bulldog” sequence towards the end of the film. Recorded by The Beatles in February 1968 to fulfill their requirement of providing four new songs for the project, the sequence was a last-minute addition, animated in just two weeks, according to Balser. “It was something that Bob Balser said he always hated,” notes Rutan, “because the animation is in a style that doesn’t seem to fit with the rest of the film.” The scene was removed at the time of release in American prints, and seen only briefly in England.

The sequence was thus not in the U.S. version Eque was working from, though Rutan was able to locate an original British interpositive containing the sequence, which he scanned and had his Indian counterparts clean, after which he placed it in the proper location in the film. “The problem was, though, we were looking at it, and I realized that when the studio had removed the sequence originally, they had created additional animation, so that when the pieces from which it was removed were joined together, there would be story continuity,” Rutan recalls. “I still had that animation in there, which didn’t fit when we placed ‘Hey Bulldog’ in. So I had to have Chris rescan additional material from the British interpositive, which has different animation before and after the song, and we all had to do that sequence over. At the end Bob was happy with what we had done with it.”

One thing certainly remained intact from the original 1969 production, evident to Rutan and his team. “The quality of the animation was even better than I expected – it just blew me away,” Rutan says. “I discovered it was truly art – hand-drawn, hand-painted art that needed to be preserved. And that’s what we’ve done.

Crafts: Post/Finishing

Sections: Creativity Technology

Topics: Project/Case study beatles nucoda film master restoration yellow submarine

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.