On Digging Through the Archives, Rescuing Reels from Storage, and Seeing Ethel Merman in Gypsy for the First Time

Few artists of any stripe have a career as fruitful and storied as the legendary composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim. A new HBO documentary, Six by Sondheim, which premiered last week, looks at the man's work by focusing on six different songs from his more-than-50-year career. James Lapine, the stage director Sondheim worked with on Sunday in the Park with George, Into the Woods, Passion, and more, directed the film and executive-produced alongside former New York Times theater critic (and Sondheim expert) Frank Rich and HBO's Sheila Nevins. Nobody — Sondheim least of all — wanted to make a traditional talking-heads documentary. They envisioned a film that would use those six tracks as guideposts of a sort to move viewers through Sondheim's career, including newly staged performances of three of the numbers. So Jarvis Cocker does "I'm Still Here" in a nightclub segment directed by Todd Haynes, Audra McDonald and Will Swenson are in a version of "Send in the Clowns" from director Autumn DeWilde, and Sondheim lends his own presence — alongside Jeremy Jordan, Darren Criss, and America Ferrera — to Lapine's restaging of "Opening Doors."

The task of integrating the musical numbers with a veritable avalanche of archival footage fell onto the desk of editor Miky Wolf at Big Sky Edit in New York. Wolf found himself making sense of the archives in much the same way Sondheim said he made sense of his notes for song lyrics — by making lists of his raw material, scouring it for patterns and connections, and then using those as hooks to pull the pieces together and really start telling the story. We talked to him about digging for film that had never been seen before, cutting in every format known to man (and some that aren't), and what it was like to work with a genuine giant of the musical theater.

Were you an experienced documentary editor when you signed up for this project?

When I started in the business, I was hired as an assistant on a film called Comedian, a Jerry Seinfeld documentary that Chris Franklin cut here at Big Sky back in 2001. So my first couple of years were assisting him, and that was my first experience at editing anything. We do mostly commercials here, but in the last few years there has been a push toward more documentary-esque spots. But what James [Lapine] was looking for was not a traditional documentary editor. In fact, he was looking outside the box — which is kind of how he found me. I got the gig almost because of my lack of traditional documentary editing. It was one of the dictates Stephen had when HBO and James approached him. He said, "Well, you can make it as long as it's not a typical American Masters-style documentary." Not that there's anything wrong with American Masters, but he wanted something different.

The last American Masters I watched was on Woody Allen, and it was 192 minutes. You could easily have gone that long or more with Stephen Sondheim, but instead this film is about 86 minutes. Was that something you talked about going in — keeping it from sprawling?

In our first conversations early on, before he left me alone to dive into 100-plus hours of footage, James was most interested in pacing. He wanted this thing to move like a freight train. He wanted to avoid the traditional style — dialogue, cut to a still, bring up a music cue from one of the shows, move in — avoid that at all costs. It was about opening me up to think of creative ways to move the story along and keep up the pace. But we never talked about length in terms of running time. We did have cuts that were longer and we ended up taking material out — not for length, but because we would veer off on a tangent. We were already introducing musical numbers that were taking you out of the narrative, so we wanted to stay with [Sondheim] and let his momentum carry the whole thing as much as possible. That's why it stayed short and feels as quick as it does. And I like that. If you're left wanting a little more, that's OK.

It's one of the first rules of showmanship — always leave them wanting more. The pace of Six by Sondheim is so propulsive, with the cuts always pushing it forward. I was wondering — did you make a conscious decision to be ruthless?

No, that was not a conscious choice. What I find is that Steve is ruthless. I don't mean emotionally or physically. But he operates at such a high speed intellectually and verbally. He's obviously a brilliant linguist, and it was important to me to maintain that speed. I feel that he has a tempo the movie reflects. The pacing you feel, the rhythm, and the motions you go through are all part of what Steve is. James helped me shape that, knowning the man more.

We worked on segments of the film independently. The first one was "Send in the Clowns," and the cut really didn't change much. Once we established the ability to move among all of the interviews, TV broadcasts, and film clippings dating back to 1957, piecing them together and creating a train of thought between them, his rhythm carried it. You can't hang with him. He doesn't hang. He's thinking three sentences ahead of what he's saying. He is so unbelievably sharp and eloquent, and to see his craft with that scope is mesmerizing. It was about staying true to that. If he's staying two or three thoughts ahead of himself, I want to stay an edit or two ahead of myself. It's the propulsion of thoughts and the juxtaposition of clips that gives you a real sense of who you're dealing with.

Stephen Sondheim in front of Georges Seurat's A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte at The Art Institute of Chicago.

Many times a documentary's structure comes out during the editing process, but it sounds like you had a structure in place before you started working on this one.

Yes, Frank [Rich] and James had set the structure. James had given me the six songs in the order he thought they should be in. And he had some insight on ideas that might take us in and out of the songs, which was helpful in terms of understanding the task we set out to complete. I built the segments independently at first just to figure out what we had. I wondered, how can I make something interesting about poetry and lyrics? And I would do what Steve does [as part of his lyric-writing process]. Instead of making lists [of words relating to characters in a show, which would eventually suggest song lyrics], I was looking at select sequences and seeing what related among them. There's a serendipity to comparing words when you've made those lists, and that also happens when you're cutting. So that was how it took shape, but the order of songs was set. The numbers were very well thought out in terms of what they were going to allow us to do, and how they would get us into his life. Clearly, people argue about whether they are his most popular songs, and I think James and Frank said, "We are not saying these are six of his most brilliant songs." But they showed a variety and diversity in his work, and allowed us to look at different eras in his career.

Stephen Sondheim on Camera Three, a CBS show hosted by James Macandrew, in 1965.

Let's talk about archival materials. How did you select what you used?

There was a researcher, Judith Aley, who spent a good amount of time collecting everything that existed on Stephen Sondheim — everything that aired on CBS, ABC, and NBC, every show since 1957 when West Side Story hit. And I had some home videos of his. When you get to the 100-hour mark, you're including the specials and films made about all of the shows. So I was given a lot of that. The mountain of terabytes just seemed overhwelming at first, but it was captivating as soon as I started going through it. I was sucked into the guy's thought process. I had a connection at the Paley Center for Media, Jane Klain, who is a walking encyclopedia of media, but especially Sondheim media. So I'd ask her about anything I'd find that I liked, and certain clips came from her putting me in touch with the people who shot the original film. The Hart Perry footage showing Steve with all of those chess pieces from the early 1970s, that stuff was sitting in a storage closet in Woodstock. Perry had cut it for WNET and then put it away. He had mentioned to Jane that he had all this footage, so we convinced him to bring it in, and we synced up as much as we could and had it all transfered.

And there was that great footage of Ethel Merman performing in Gypsy that no one has seen before. There is no existing film footage of Ethel Merman performing in that role that anyone knows of except this piece. Ray Knight, the guy who shot it, was from the South, and his mother had given him a 16mm camera for his birthday. He came up here and would walk around New York City with a 16mm camera, just shooting stuff. Some of the B-roll we use in "Opening Doors" is his footage. And he went into Gypsy and shot that stuff with Ethel Merman. Somehow, Miles Kreuger at the Institute of the American Musical [in Los Angeles] got this guy's film and has been sitting on it for years. Jane said, "You can call him, but he wants to make his own movie out of that footage." We actually convinced Steve to call him — and within a day he was on board with letting us transfer it. When I showed it to Frank, he was blown away. That's a performance he never saw and he always wondered what she was like, and then you see her shakin' it up there, looking sexy and doing her thing.

But for me, I'm not a Sondheim aficianado. I never had the feeling of, "Oh, this [clip] has been seen too much." I was looking for content and emotional weight. What does it do to you? And that's why some of these things stayed in. The Larry Kert footage [from West Side Story] was just inspiring. And Dean Jones doing "Being Alive" [from Company]? I had seen that years back, but in preparing that section of the film it just floored me. I had other versions — Raul Esparza, Adrian Lester, and others — and there's no question that Jones had the most staggering performance of that song. I threw it in as a placeholder and it ended up staying. Of course, the Pennebakers [D.A. Pennebaker filmed the recording sessions for the Company original cast album in 1970] gave us permission, and Frazer Pennebaker gave us an original film print. We had every format of media ever made in this movie, from kinescope to ARRIRAW 4K.

America Ferrera appears in director James Lapine's restaging of "Opening Doors"

Was there ever a case where you had trouble tracking down a playback device that could handle a particular piece of footage?

For some reason, the kinescope from The David Frost Show was missing, and the only existing footage from that show came from John McMartin — he appears later with Yvonne De Carlo and does a dance, a pretty funny number — whose wife recorded it with rabbit ears onto this Sony reel-to-reel video recorder that doesn't exist any more. I called all the labs I knew and one lab in L.A. had the machine — at Duart, one of the tech operators said he had one locked up in some closet, but if we could pay for it he would hook it up and do the transfer. It had been transfered one other time, so the footage was out there, but it was a degraded transfer. We thought all we would have was this old 3/4-inch dub that was really awful and almost to the point of being unusable, but we borrowed the actual reel-to-reel material from the Paley Center, retransfered it, and did tons of frame-by-frame clean-up. That was pretty awesome.

James and Frank were both very involved, but they're busy guys, so I was left for large patches of time just getting on the phone and doing research. As editors, we don't usually get to do that. But at the end of the day, I was seeing holes and I wanted to fill them. Nice Shoes was a big help with a lot of the transfers. We had a little over two years to work on it — HBO never gave us a deadline until we got close enough that they could smell it was almost finished.

What system did you cut on, and what was your workflow for handling all those different media types?

We were on Avid Media Composer, and it was amazing. We managed to combine everything. The difficult part was that I was working at 24 frames, so we were doing a lot of conversions up front to get the material into the timeline. For the stuff we couldn't convert, we were just working in mixed frame rates. We started in Media Composer and then color-corrected and onlined in Symphony, so it was an Avid process from start to finish. I feel more comfortable in Media Composer anyway, but with the depth of this thing in terms of the amount of material we had — and we were pretty close to filling a 12 TB drive with everything, including renders — I needed the organizational structure and file structure that the Avid guarantees.

But the move to the online was complicated. It took months. We had screeners from our researcher, but we had to track back and find the masters. We were working with T3Media and many different licensors for three months, and going through Steve's personal collection of material, just trying to track down the best copy of everything. For certain things, I felt like we were going to have to settle. And then Patrick Lindenmaier from Andromeda Film came over to do the color-correction and the online, and he was just phenomenal. We met him on Comedian, and he specializes in film-to-digital onlining and color-correcting, but he's also a DP and one of the most brilliant technical and visual minds I know. We have a Teranex here and he jury-rigged it so we could play out of the Teranex and capture in the Avid.

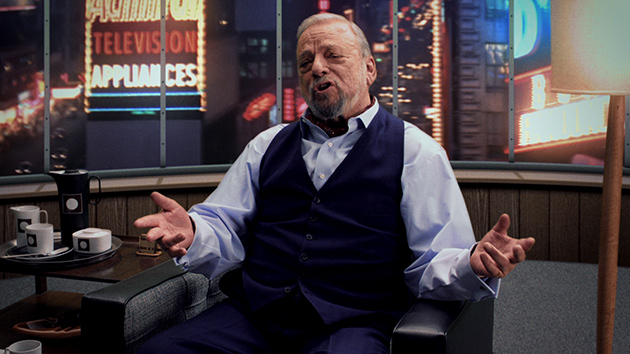

Miky Wolf (left) with Stephen Sondheim

Did you spend much time with Sondheim while making the film?

I met him a few times. Frank and James are both very close with him, but he didn't see a cut until the film was done. He and I communicated via email early on, and he offered help getting footage and with some technical questions, but I wanted to hold off on actually meeting him. When you're working on a film, you don't want to meet the actors before you're done with the cut, because you don't want the meeting to taint what you're going to do, and I was nervous about meeting him and having an experience that would affect me, so I was careful for the first year and a half. When I did meet him, it was on set for the "Opening Doors" number, and he had seen the cut and was a big fan of it. He was thanking me and I was dribbling all over him, and he was really gracious — a real mensch, thankful and also inquisitive, asking me questions about certain things. He's still the smartest guy in the room, and it was a pleasure.

Crafts: Editing

Sections: Creativity

Topics: Project/Case study Q&A big sky edit documentaries ethel merman frank rich HBO hbo films james lapine miky wolf musical theater sheila nevins stephen sondheim

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.

Leave a Reply