Starting with its opening titles, the new virtual-reality series The Possible shows how revolutionary innovation is literally all around us.

Virtual reality studio Within is known for innovative collaborations with artists on a wide range of creative projects. But the new five-part virtual reality series, The Possible, is remarkable for the way it allows viewers to explore technology in a thoroughly immersive way. “Hello, Robot,” the series premiere, was created in partnership with Within’s sister company Here Be Dragons and General Electric, and presented by Mashable.

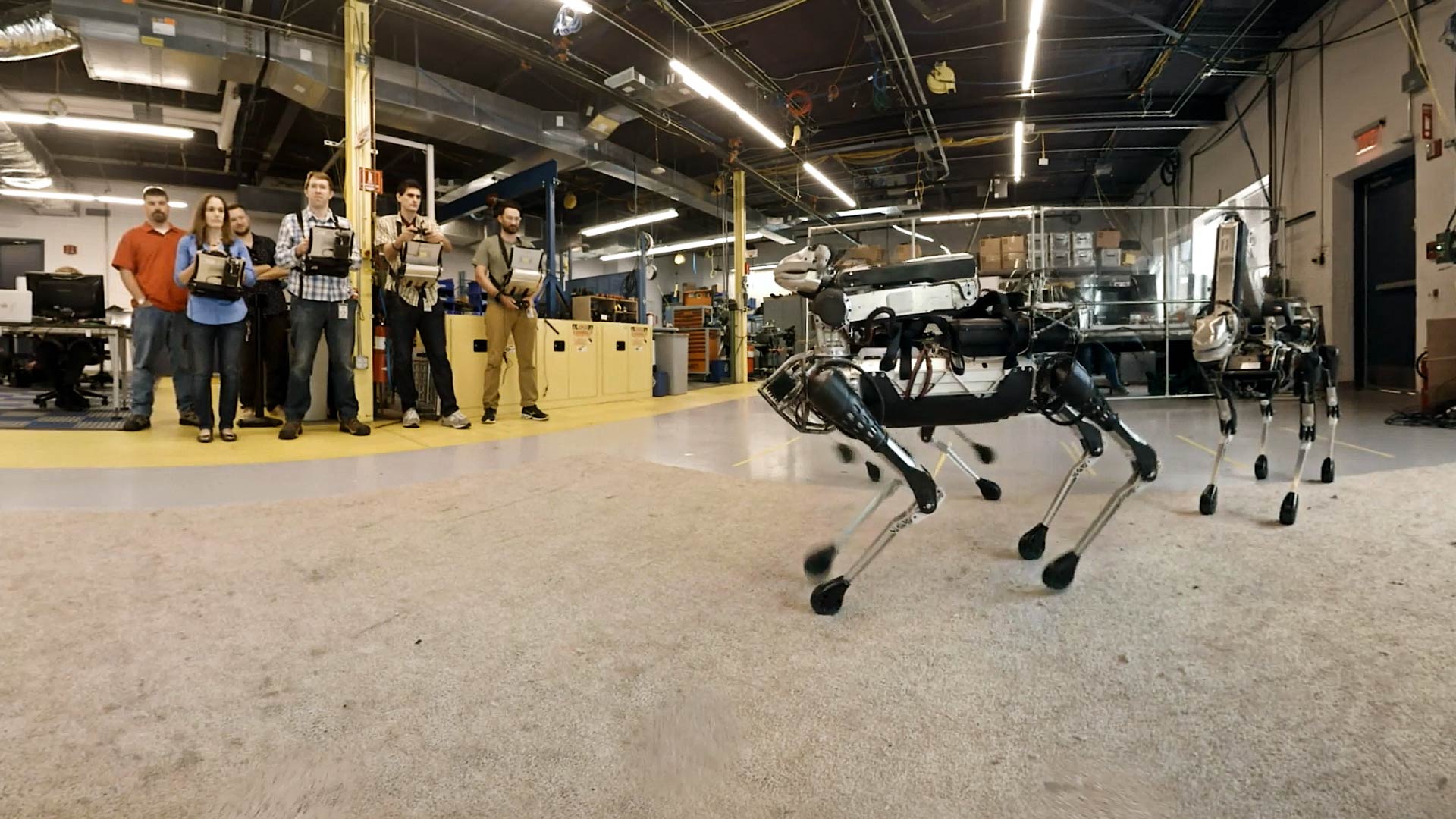

The Possible series episode “Hello, Robot” gives viewers a rare look inside the Boston Dynamics lab.

Directed by David Gelb (Jiro Dreams of Sushi and Chef’s Table), Hello, Robot takes viewers inside the Boston Dynamics lab. Normally off-limits to the public, the lab is alive with inventors building and testing out robots of various shapes and sizes. (For the best viewing experience, download the Within app.) In 360 VR, Boston Dynamics’ philosophy of “build it, break it, fix it” feels almost alarmingly real as robots crash around and malfunction in front of the camera.

Robots are seen walking along a trail in “Hello, Robot.”

The episode begins in a forest where odd sounds soon reveal themselves to be a human-like robot with a dog-like robot walking along a trail. The series’ opening titles appear next, and their stylized yet hand-sketched look is meant to convey the actual roll-up-your-sleeves work that goes into innovation of this type.

Watch the Video:

Brandon Parvini used Maxon Cinema 4D to convert phong and edge break selection to splines in order to create by hand the linework for all of the objects in the titles.

The goal was to create titles with a hand-sketched look.

Los Angeles-based BEMO used Maxon Cinema 4D, Otoy OctaneRender, Adobe After Effects and HTC Vive, as well as Virtual Desktop, an application that allows artists and other creators to use their computers in the VR environment, to create the titles in stereoscopic 360 VR. Here Brandon Hirzel, BEMO’s founder and creative director, and Brandon Parvini, BEMO’s project lead, explain the challenges they faced when making the series’ opening titles, and how the look and feel relates to the exceptional series itself.

StudioDaily: How did you get involved with making these opening titles?

Brandon Parvini: I’ve worked David Gelb in the past, most recently on The Lazarus Effect, but also on the documentary A Faster Horse, where I developed a look he really liked. When this opportunity came up, he reached out and we went in to look at the footage and talk about the story, and from there we jumped into design.

How did they describe what they wanted the titles to be like?

Brandon Hirzel: That’s interesting because things changed over time. Our early creative discussions were based on the look Brandon had done for A Faster Horse, so we went with that and built everything out to have a polished, blue-black look. Initially, the clients loved it, but when they cut it into the project they felt that the look of the titles didn’t match the look of the footage so they asked us to make a pretty drastic pivot in creative direction.

The original look was built using C4D’s Sketch and Toon and Physical Renderer.

They wanted us to create something with the feel of inception, something that felt expansive yet scaled back to show the process of planning and sketching, like the first moment artists put pen to paper. In that moment, anything can happen. That’s what they wanted to show. So we started over.

Parvini’s experience with optimizing models while working on A Faster Horse proved invaluable when working on The Possible.

Parvini: It was just Brandon and I working on this, and we didn’t have much time, so we couldn’t change the models too drastically. Each one illustrates something from each of the five episodes in the series — a robotic arm, satellites, a drone copter, an engine and a space capsule. We wanted to make them feel authentically drawn, so we created some texture assets by crumpling up paper and scratching lead on a paper, just to get some natural analogs into the mix.

Title imagery needed to work as well flat as it did in VR, Parvini focused on creating a VR experience that suggested complexity and depth.

We fed those into a shader system and mapped it to an inverted Dirt shader, which is similar to an inverted Ambient Occlusion shader, and got this really fun hand-sketched look. I used C4D’s MoGraph cloner to strap on auxiliary sketch lines and a simple planar effector that wiped them on and off like a big eraser. We were really happy with how things ended up and, thankfully, so was the client.

Describe the challenges you faced making the titles in stereoscopic 360 VR.

Parvini: 360 VR is a strange place to dwell. It’s engaging to be inside, but as artists, we have been telling stories and creating content since day one in a very specific medium — flat screens. Now we need to create a place where a viewer can be looking anywhere at any point in time. It’s kind of terrifying. You have to make sure everything is worth looking at, but you also have to drive viewers’ eyes where you want them to be so the story you want to tell is clear. It’s been exciting to try to figure out.

Octane’s raw panoramic output (above) served as an atlas for what would be visible to the viewer wearing a headset. “After a while, we were able to see the alignments and read outputs without have to constantly be under the hood,” Parvini says.

Hirzel: The process of blocking out animation and storytelling for 360-degree video creates a challenge all its own. Usually when you’re designing and opening title sequence, typical filmmaking techniques play a large role — the pace of the edit, different camera angles, swapping lenses, racking focus and changing lighting. But when you’re in a 360-degree space, you have to be creative in a different way to get the right look and feel. As Brandon was saying, you have to motivate the viewer to look without being too obvious. We would constantly be testing previews in the headset to see what felt natural versus what felt forced.

Created to look almost like blueprints, the titles helped convey the hands-on complexity of innovation.

Those preview renders needed to be low-res, because you have to go through that process several times before you do the final render. Files are so massive for the final deliverables, and the render times are so significant that, unless you have a really relaxed schedule, you don’t have time to wait around. Octane’s workflow significantly improved our previous experience with VR, and with the help of our multi-GPU setup, and Cubix Xpander, we were able to maximize our render times on our previews and final stereoscopic outputs.

Parvini: Now that we’ve worked in stereoscopic 360 VR it’s hard to imagine wanting to experience VR any other way, because the stereoscopic view lets you see the parallax and depth of the objects moving around you. It’s like you’re really there. It’s much more immersive, and there is palpable weight to the objects in the scene, creating a sense of mass and scale.

Each piece of a scene was built with significant detail so that objects could pass close to the viewer.

How did you review what you were doing in stereo?

Parvini: We did our reviews with an HTC Vive headset, which was a really big deal because things would look good on the computer, but then you’d put the headset on and see that the engine was way too close to the camera, or some other thing needed to be moved down by your ankles. VR is still very much the Wild West. There isn’t a great catch-all solution for doing simple playback of stereoscopic files in VR in a review-style format. We bounced between Whirligig, a video player for the Vive, and Virtual Desktop.

Hirzel: The exponential growth of technology, and what we’re able to do with software right now is amazing. Five years from now, what we’re doing now will seem silly and we’re super excited to be a part of what’s happening.

Crafts: VFX/Animation

Sections: Creativity

Topics: Project/Case study 360 VR cinema 4d htc vive Maxon title design VR

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.

Leave a Reply