Some of the pre-release buzz around The Irishman was … skeptical. Yes, director Martin Scorsese remains one of the most celebrated filmmakers in the world, but wasn’t he repeating himself by making another mob movie starring Robert De Niro? How could he justify a three-and-a-half-hour running time? And what about reports that the film was using de-aging techniques to allow De Niro, Joe Pesci and Al Pacino to play younger versions of their characters in the film? Was Scorsese’s character-and-performance-driven approach compatible with VFX-heavy filmmaking?

Well, The Irishman took the New York Film Festival by storm on its world premiere and hasn’t slowed down. It enjoys a nearly pristine 97% fresh rating among critics reporting to the Rotten Tomatoes Tomatometer. After opening in limited theatrical release on November 1, it expanded to more than 500 screens over the Thanksgiving holiday weekend, despite being available for streaming at home, according to IndieWire. (Netflix hasn’t yet released box-office returns or streaming viewership figures for the film.) And yesterday, it won Best Picture of the Year from the New York Film Critics Circle, putting it in something close to pole position as awards season gets underway.

Clearly, its extensive use of de-aging technology hasn’t compromised The Irishman‘s ability to connect with audiences.

In planning and supervising the film’s visual effects, Industrial Light & Magic’s Pablo Helman executed a clear brief from Scorsese and the film’s cast — no markers on faces, no mocap suits, no mocap stages. The technology needed to be unobtrusive, and Helman needed to stay out of the way of the performances. He did it by using unique three-headed camera rigs designed by ILM in collaboration with cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC, and Arri. Each rig holds a primary Red Helium camera along with two witness cameras — Arri Alexa Minis altered for infrared cinematography. The three camera views were fed into ILM’s proprietary Flux software, which turned them into 3D representations of the actors’ facial performances. The resulting performance data was then applied to 3D models of each actor (they were captured on a special light stage before principal photography began), creating a digital version of the performances captured on set that could be retargeted to younger likenesses of the actors’ faces ILM had prepared.

Scorsese himself took a keen interest in making sure the retargeted performances accurately reflected what was captured on set, ensuring that the film’s emotional payload wouldn’t be lost behind carelessly applied digital make-up. The resulting effects, which help unite a sprawling narrative that criss-crosses decades in one man’s life, are unlike anything movie audiences have seen before.

We talked to Helman in more detail about the project, the process, and what it means for the future of facial performance capture.

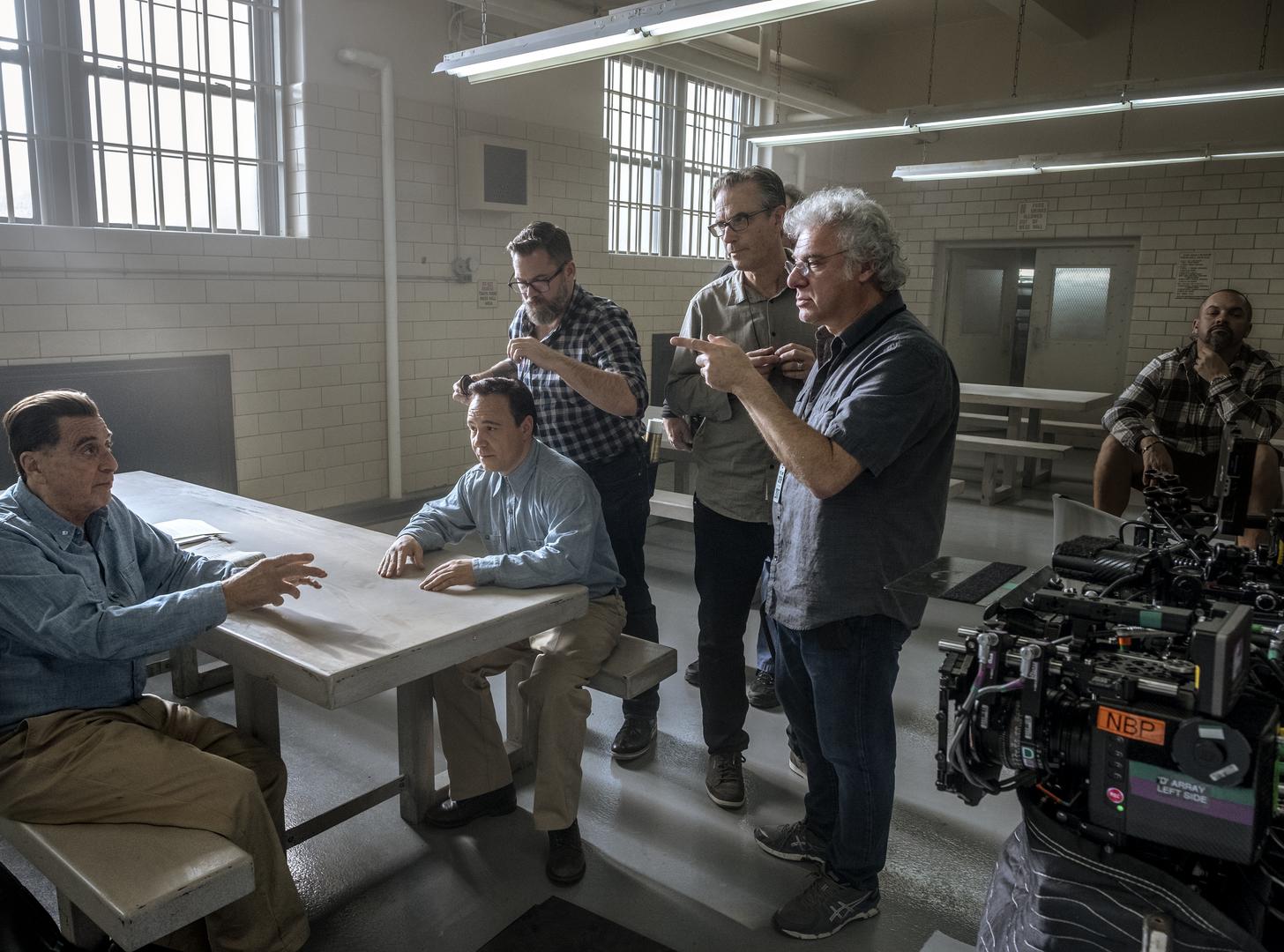

Pablo Helman (foreground) with Al Pacino and Stephen Graham (seated at table) on the set of The Irishman.

Niko Tavernise / Netflix

StudioDaily: How did you get the job? I know you had worked with Scorsese before [on 2016’s Silence]. But did you have previous experience with de-aging techniques?

Pablo Helman: I started on this project in 2015, four years ago. Before that, I had been working on facial capture technology for about five years on different projects here at ILM. In 2015, everyone was using markers on the actors faces, helmets with cameras — even now, everyone uses that technology. And I knew that, naturally, the next thing in facial performance capture would be getting rid of all the technology that is burdening the actors.

When I was working with Marty in Taiwan on Silence, we started talking about the technology and he mentioned this project. He sent me the script overnight, I read it, and I said, “I’m in.” It was the perfect vehicle to focus completely on performance. Performance is always a part of visual effects, but in this movie, the whole thing is performance — close-up work, shots that are forehead to chin, very subtle performances, dialogue work, and violence, but in a talked violence kind of way, where you have to emote. Robert De Niro said, “If we’re doing this, I cannot have markers on my face, I don’t want to wear a helmet with a camera, I don’t want to wear grey pajamas. I want to be on set, with theatrical lighting. I don’t want to go later on and record something on a mocap stage without my acting partners.” They said, “You figure it out and call us when you’ve got it.”

So we worked for two years developing software to capture performances without markers on the actors’ faces on set. We developed a piece of software that captures the lighting and texture of whatever is in front of the camera and converts it to 3D geometry. This is the first time that has been attempted. There has been a lot of projects working with facial capture, but this is the first time we’ve gotten performances out of lighting and textures with no markers on set, keeping the technology away from the actors.

Together with the software, we had to develop a way to capture that performance. We designed a three-camera rig where the center camera is the director’s camera, and on the left and right were two witness cameras — but they were film-grade cameras, Alexa Minis. And they were infrared cameras that also threw infrared light onto the actors and neutralized the shadows. And our software looks at the three cameras and triangulates whatever the cameras are seeing into 3D geometry that we render and use to replace the faces of the actors.

How did the Alexa Minis work as infrared cameras?

We worked with Arri in L.A. to modify the cameras. Every camera has an infrared component, but it’s usually filtered because we work in the RGB spectrum. If you take the filter away and modify the camera’s software and hardware, then the cameras become completely infrared. We also worked with another company to develop a proprietary ring that goes around the lenses and throws infrared light. We throw that light, the cameras capture it — and not any other spectrum — and we’re rid of all the shadows.

And you’ve got multiple perspectives on the face, so that’s how you get the 3D data, right?

The software is called Flux. It incorporates the three cameras and triangulates the three different angles to get a 3D render of the actors on a per-frame basis. That is the main difference between this and anything that has been done before — the combination of the software, markerless capture on set with theatrical lighting, and the rig calculating geometry from light and texture. This is brand new.

DP Rodrigo Prieto behind the three-headed camera rig used on the film.

Niko Tavernise / Netflix

So cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto didn’t have to worry about how he was lighting faces? You were able to get this data independently of what he was doing with lighting to tell the story?

That’s the idea. Obviously, if we’re working with infrared light, incandescent sources are a problem, but Rodrigo was very flexible. Whenever possible he used LED fixtures. But the majority of the film has a very warm and filmic look, and all of that is incandescent sources. We worked with all that and tried to be as non-intrusive as possible. Same with the rig. We made the rig 30 inches wide because that’s the measurement for a U.S. door frame — 32 inches — and we knew we had something like 200 locations. So Rodrigo could go right through the doors. We didn’t want to interfere with anything Marty and Rodrigo were doing. The whole idea was to base it on performance and take the burden away from the actors.

So it was your job to be essentially invisible during production.

Definitely. This is one of the smoothest projects I’ve been on in the last 30 years. It had to be, because Marty is so exacting when it comes to performances. Actually, this is the closest I’ve been to art. There is, really, no compromise. Where the director says the camera goes, there it is. There is no “we can’t do that.” We worked with Rodrigo to get the weight of the rig down from 84 pounds in the beginning to 64 pounds, so we could put those three cameras on any rig that they wanted to use, including Steadicam. Our job was to be as invisible as possible. I think Marty was really pleased with the results.

Robert De Niro today (left) and his character at 41, as seen in The Irishman.

Netflix

What was the pressure like on you, in terms of actually executing the effects and replacing the faces in a way that was going to be realistic and expressive and emotive and, hopefully, not draw viewers out of the film? How did you approach that challenge?

It was really important for Marty not to just rewind 30 years and look at Jimmy Conway [De Niro] from Goodfellas, or Joe Pesci in Home Alone or Casino. He designed the characters to be younger versions of the characters on screen. Frank Sheeran has a wider face than De Niro had at 40 years old. And he has blue eyes because the original Frank Sheeran had blue eyes. Marty is very exacting when it comes to details. Pesci was never that thin at 53, but he is in this movie, because that’s the way Marty designed the characters. So design was one thing. It was the same with the behavior. It was really important that the characters looked as natural as possible, so we did not use any keyframe animation to change any of the performances. That is a big difference, for a director to say, “Whatever the performance is, I’m not going to change anything.” So there were no animators on this show. What you end up with is the raw performance by the actors, and then a reinterpretation or retargeting of that performance that is designed to look like a younger version of those characters.

A younger version of the characters, rather than trying to mimic what the actors used to look like — or building a CG model based on frames from Taxi Driver or whathaveyou.

We did take a look at that. We ran it through an AI program we have that lets us render a picture [from a de-aged performance] and then run it through a database of thousands of frames and sequences from all these different movies, and the computer spews out a bunch of frames from different movies that match. We did that as a sanity check, not necessarily because we wanted to put it in the movie. But it’s a great aid, and AI is going to be part of everything that we do in VFX for the next 10 years.

Joe Pesci on set (left) and de-aged, as he appears in the film.

Netflix

How intense was Scorsese’s involvement with what you were doing? I read an interview with Quentin Tarantino, where Scorsese made a reference to having been working so hard on the VFX over the last six months that he hadn’t actually screened the project as many times as he normally would have.

True.

It sounds like he was really in there, focused.

He was. But also different from any project I have been on was the fact that the reviews with Marty were not intermediate reviews. I would never show him a work in progress. It was important for him to see the render with the right light and the right texture and the right age. We would do reviews with side-by-sides, where the left side would be my render and the right side would be my plate. These reviews were about performance. His main comments didn’t have to do with behavioral likeness, because we were always OK on that front because of the modeling we had done. The majority had to do with texture, skin, how old the character was in a specific shot. It was like a puzzle. We would put one shot in there, making it as faithful as we could to the age for the narrative, and as we worked on the other shots, we’d put them right next to each other, and then maybe adjust the shots we had stopped working on until everything fit. It was an incredible process. Marty was completely involved with performance, and I had to understand what he was looking for. It’s funny — the difference between a smile and a wince might be a couple of pixels. And it’s all about how Marty felt about that performance. He’d say, “Well, you know, he needs to feel concerned, and right now he feels a little surprised. Concerned but surprised. I just want to get rid of the surprise.” We would go into the software and analyze what made him look surprised as opposed to concerned, and dial up the sensitivity of the software to pick up certain things.

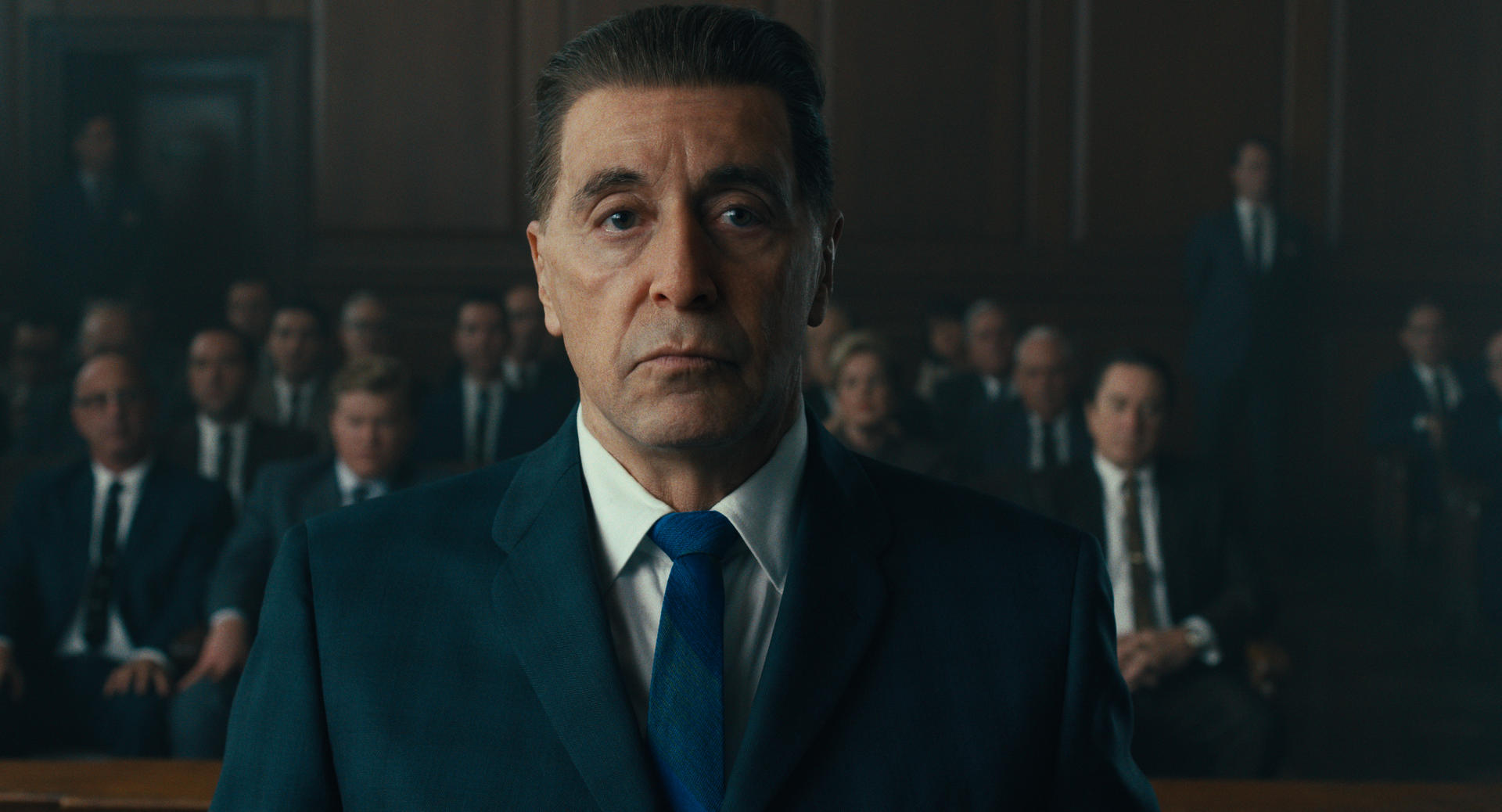

De-aged Al Pacino in The Irishman.

Netflix

Do you expect this process to become the standard for this kind of work?

The most important thing is to make sure everyone understands how different this is from everything else that’s been done before, and how important it is for actors. The achievement here is markerless, on-set performance with theatrical lighting, and I can’t wait for actors to take a look at this and say, “Wait, does that mean I don’t have to wear 138 markers on my face? I don’t have to spend two hours in makeup, and I can actually act with my acting partners as opposed to going somewhere else?”

So you feel this really points the way to the future.

We’re going to go that way. Naturally, we started with just performance as reference, then we put some markers on grey pajamas, then we put markers on the face, but technology is at a place now where there shouldn’t be markers on everyone’s faces. I know a lot of people are saying, “Maybe this is more expensive.” But it’s not, really. All the expense we had was research and development, and we’ve done that already.

How did you feel toward the end of the project? No matter how confident you feel about your work, there must be an X factor in how it’s received by the rest of the world. In this case, it’s been overwhelmingly on the positive side, but …

Definitely, it has been. But it’s always the same. You never finish a project, you only abandon it because you run out of time or resources. There is always something I could have done differently, but the main emphasis is on performance, and we are really happy with the performances. Also, we accomplished what we had set out to do, which was to give the actors the freedom they needed to perform in truth. Actors always talk about truth. They would like to be in truth. When they are with each other on set with no markers, they are in the moment and you get the best performances. That’s something I learned over the last two years. I’ve been working with actors on mocap stages and in blue-screen work, and there is something that’s always there but is difficult to put your finger on. Research tells us the body does what the eye does. If you have an actor acting with a partner in front of each other, and they check each other to make sure both actors understand what they’re saying, they’re assenting, they’re going with the scene. The actors always check out the set around them and adjust to the set, and that kind of behavior is not there when you’re on a motion-capture stage. Even if another actor is there, the setting and lighting are not the same. They’re not in the moment. And that makes a difference.

It’s a great study in human behavior and human communication. What makes a face communicate something? I speak two languages, and we all read and write and we have all kinds of visual cues, but sometimes we’re in a meeting and everybody gets a different idea of what happened in the same meeting. That’s how complicated communication is. I have three cats, and it’s incredible to me to take a look at two cats. One might be in one corner and the other in another one. They look at each other, one moves and the other takes its place. It’s just one look. And we have all these languages, reading and writing and all the cultural stuff, and we still can’t communicate with each other.

So you’ve just completed a massive experiment in human communication and the nature of performance, on top of everything else that went into this.

Definitely. I think you learn a lot about humanity.

Robert De Niro (left) and Joe Pesci in The Irishman.

Netflix

Crafts: VFX/Animation

Sections: Technology

Topics: Project/Case study Q&A de-aging Martin Scorsese performance capture

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.