Tedeschi: I did an episode of The Blues with Marty titled "Feels Like Going Home." It was a mini-series that aired in 2003 with different directors doing different episodes. I was living in L.A., working on The Osbornes at the time, and The Blues' executive producer recommended me to him.

What do you think sets Scorsese's documentaries apart?

He's always championed a style of filmmaking that's very emotional. It's not sentimental. He's really attracted to compelling stories, compelling conflicts and compelling people. But the way he tells the story is very emotional.

A lot of people think of documentary film as just being for information – "informational," as Marty would say. He likes to include both information and interview material that give you a sense of the person or of the time in which their story takes place.

Marty's been making documentaries for a long time, and he does it in a way that he describes as very "liberating," free of artifice. In his 1974 film, '"Italianamerican," he basically picked up a camera and shot his parents in their apartment. I think he was sick of the way films were being made. When he was cutting, he just went, "You know what? I'm just going to jump-cut this. It doesn't need to be elegant," which is something you see in "No Direction Home" and elsewhere. He's convinced me that a lot of this artifice doesn't matter. What matters is the heart of the story.

What's the process of creating the narrative like? Is there a script?

Every project is different. But, no, there is no script, no writers. The material comes in, both interview and archival, and we both review it. I'll look at 100 percent of what comes in and Marty looks at a lot of it, and then we'll talk about it, and I'll cut a scene out of it. Then we'll work together on it.

Does he give you any specific direction at that point?

I might spot, for example, a good story that an interviewee will have told and suggest we use it. He will have seen it, too – he might say, "Oh, yeah," or he might say, "Yeah, but you have to be careful about this." Not because of sensitivity of what's being discussed, but he might think it's sentimental, or perhaps just not that interesting." He might also, as we're working, suggest, "You know what would go really well with this is this piece over here."

That's the joy of working on a film like this. You do get to experiment and you get to play. I think that's why he loves doing documentaries – because he relishes being able to experiment in the cutting room. It's a lot of fun for him, to take his time with it and let it evolve and develop at its own pace.

How do things progress from there?

We think that to make the film more powerful, it's good to make it feel like the film has scenes to it. So I'll begin creating scenes as I cut. I'll evaluate clips, to get a sense of their value, honing them down into shorter pieces, and then begin to structure it.

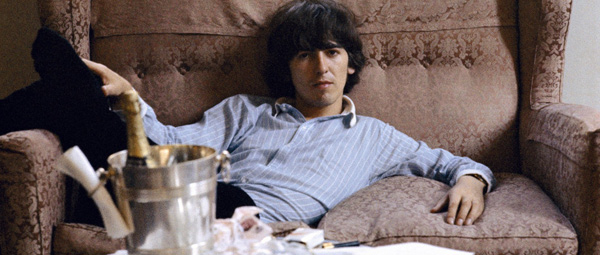

How did you begin on the Harrison film?

At first, actually, I began cutting the All Things Must Pass [Harrison’s first solo album] section. But it was disconnected from everything. It wasn't very satisfying to start in the middle of the film – it was a little disorienting. So after that, I went back and we started at the beginning, his early life and the Beatles period.

There's an incredible amount of rare archival material in the film. Did you do a lot of restoration work on it?

That was incredible, particularly the material from the Beatles era. No one had made this complete an attempt at finding clips since The Beatles Anthology in 1995.

Olivia, George's widow and one of the film's producers, also provided a good deal of photos and home movie material shot on a variety of formats. The tulip sequence, which you see in the beginning of the film, was a home video George shot himself, with the camera on a tripod in his garden. It was shot on ¾-inch [tape] as a lo-res home video. There's another of George on his 1974 Dark Horse tour, which was a rare two-inch format.

Much of it had been transferred to DigiBeta a few years ago, but we re-transferred it to 4:4:4 HDCAM SR. We did a lot of work to maintain the integrity of the image.

What do you think are the most important things you've learned from working with Martin Scorsese?

He has a really visceral, immediate reaction to film. To any footage. And he's made me much more aware of how important that is. So that if you see something the first time, and it terrifies you or it moves you or makes you laugh, you have to remember that reaction and you have to use that. What you first think is compelling, and what is compelling about that, that's what's going to make your film special.

Crafts: Editing

Sections: Business Creativity

Topics: Feature Project/Case study David Tedeschi documentary Martin Scorsese

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.

Leave a Reply