How Color Mill Custom-Built a 'Digital Lab' in Utah

When Cummins said that, he had no way of knowing what variety of formats would eventually be involved. Color Mill embarked on an SI-2K workflow, but soon footage shot with the Canon EOS 1D Mark IV came through the door. Super-slow-motion footage from an IDT Redlake high-speed camera showed up. And so on. The team at Color Mill took it all in stride. “We knew that as long as we made sure we were able to take whatever they threw at us, archive it and get it through editorial, we’d look very good,” says Russell Lasson, colorist at Color Mill and digital workflow engineer for the project.

Cummins is more blunt. “Our mission statement was not to screw up,” he half-jokes. “If we didn’t make any mistakes, we would be successful.”

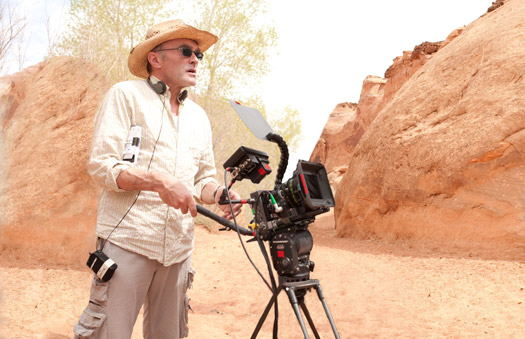

Danny Boyle on set with the SI-2K.

Not Your Ordinary Story

127 Hours is the harrowing true story of canyoneer Aron Ralston, played in the film by James Franco. While rock-climbing in Utah, Ralston got his arm pinned inside a canyon by a large rock. Trapped for 127 hours, he finally resorted to desperate measures, sawing off his own forearm to free himself.

The canyon was recreated on a stage in Salt Lake City, but Boyle also wanted to shoot in the actual canyon where the accident occurred to ensure authenticity. During camera tests, his team captured shots with very wide-angle lenses positioned just a couple of inches away from actors’ faces. The production needed support for the digital cameras that could get those kinds of intimate shots, as well as a post-production timeline that allowed editorial to start work on the film immediately in anticipation of Fox Searchlight’s planned October release date. Color Mill set Boyle’s editorial department up on site, and arranged what Lasson calls “a full digital cinema processing lab” allowing for archiving of footage, creation of editorial files, cutting Avid rushes, and 2K QC screenings.

Shooting at Double Time

Two camera crews shot five-day weeks, which kept Color Mill open essentially 24/7 to handle the massive amounts of data being created. The majority of the film was shot on the SI 2K Mini (provided by HD Camera Rentals in L.A.) by cinematographers Anthony Dod Mantle and Enrique Chediak, who recorded uncompressed 12-bit RAW files using a CineForm codec. “That codec was really designed for special-effects work, like green-screen footage,” Lasson explains. “But when Anthony Dod Mantle was screening it on our 2K projector, he said he loved the uncompressed codec, and he made the decision to shoot with it. So we ended up dealing with quite a bit of data.”

Recording that much data is a little like trying to collect rainwater from a hurricane. 127 Hours caught it in a very big bucket: the CineDeck solid-state data recorder. “That was about the only thing small enough in form factor but with enough speed to handle 83 MB/sec consistently for the data rate they were recording at,” Lasson says. The CineDeck drives could record about 20 minutes of footage, but the filmmakers generally stopped at around 15.

That’s another emerging custom of high-bandwidth digital cinematography – the digital recording device is filled up and swapped out in much the same way as mags of 35mm film. “I tell this to all filmmakers, whether they’re shooting with the Red or the SI 2K – stop every 10 to 15 minutes and treat your memory card like a digital negative,” Cummins says. “If a drive or SSD card goes bad, you lose 15 minutes of shooting instead of a whole day.” That introduces another wrinkle that every solid-state shooter understands: the need to cycle data off the memory chips, which are re-used by the production right away.

“On set, they would copy the solid-state drives to two shuttle drives, and those shuttle drives would come to us,” Lasson explains. “We would not clear them – that is, allow them to erase the on-set copy – until we had gone through and processed all the dailies on the shuttle drive. That turnaround was intense. We had access to a limited number of solid-state drives, and, at times, we were being asked to clear the on-set drives in under 24 hours so they could start using them again. It really paid off for them to have us [working] locally.”

Cummins underscores that point: “If they had used a lab in L.A., they would still be shooting now. We had to recycle material very quickly to keep the production going forward.” On set and in post-production, the team used 1 Beyond Wrangler portable tapeless ingest systems to copy all of the data – roughly 300 GB per hour of footage.

The Redundancy Tree

Color Mill created a “redundancy tree” that made sure multiple copies of every piece of footage were always available. The “camera negative,” in the form of a solid-state drive, stayed on set, but two copies would come to the facility on hard disks. Color Mill backed up the footage on LTO tape and shipped a copy to Fox. “At that point, the media lived in three different locations,” says Cummins. “We spread the assets around for protection.”

“I was really impressed with Cache-A [archive appliances],” Lasson adds. “We were using LTO-4a, which records in TAR [a compressed format associated with Linux and Unix operating systems] but doesn’t require people to use Linux. They’re self-contained, networkable Linux boxes that accept direct-attached storage for archiving directly from shuttle drives. It was a really good workflow.” For review purposes, Color Mill uploaded H.264-encoded 720p video files to Fox, delivered DVD dailies to production, and provided Avid DNxHD 36 media files to editorial.

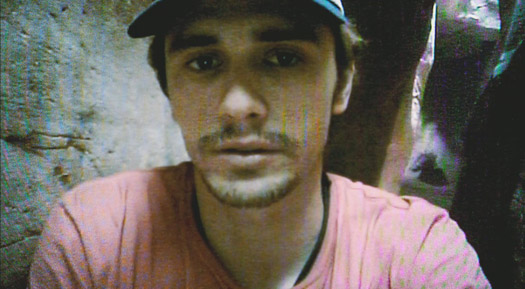

James Franco was shot on tape to simulate Aron Ralston’s video diaries.

Finessing Formats

In addition to ensuring redundancy, Color Mill had to make sure the editorial department got the material it needed quickly despite the production’s multiple formats. Each production unit had multiple SI-2Ks, but a lot of footage was also captured with the Canon 1D, shooting either in H.264 video mode or in burst mode for stills.

“In burst mode, we calculated the camera was shooting at 10fps,” Lasson says. “It had no timecode reference, it had no reel names, and clip names were somewhat random. That’s a challenge, because you have absolutely no reference for where it came from when it gets into the Avid. We designed a whole workflow to track where the frames were. Editorial could pull the drive and look at the original frames if they wanted to.” The burst-mode footage was designated as running at 12fps so that editorial could easily integrate it in the Avid at 24p. Custom workflows were developed to get each bit of footage onto that 24p timeline.

And the different formats just kept coming. The production used MiniDV to recreate some video messages Ralston shot during his real-life ordeal, and at one point even busted out a VHS-C camera. The Color Mill team just hunkered down and enjoyed the ride. “After that, we expected anything,” Lasson recalls. “They weren’t constrained [in their choice of shooting formats] by any forces. We just rolled with it.” “We thought we were going to be doing an SI-2K workflow at first, but then the Canon Mark IV came into the equation, and then the Redlake,” Cummins says. “And then it was, ‘Well … bring it on.”

35mm Was Not an Option

Dailies were viewed on set, but not in a proper screening environment. “I imagine they would have screened dailies if they only had one crew,” figures Lasson. “But Danny Boyle was never available. We screened all the footage here to make sure everything was in good shape, but it was so grueling to manage those two crews that it wasn’t feasible [for them to screen dailies at Color Mill]. We were two or three miles away from the stage, and breaking away for even that much time was painful for them.”

“The DPs did come in on occasion,” says Cummins. “The VFX supervisor came in, and sometimes some of the DITs came in to look at issues that arose so they could evaluate their options. It was handy having a 2K projector and a 20-foot screen so they could really see the image.”

Cummins also notes that QC is more time-consuming for digital footage. “When you shoot on film, you send it to the lab, and you get a negative report,” he explains. “What are the DMax and DMin levels? Are there any scratches? All that’s measured through optics, and it’s done pretty fast. But with digital cinema, and especially with this codec, you can’t produce a negative report without giving it a 100-percent lookthrough. You’re looking at the CMOS sensor, you’re looking for shutter errors, dead pixels, and noise patterns, and that has to happen in real time. A digital negative report is a whole different monster.”

From a budgetary standpoint, it all adds up – despite the obvious savings on film stock, it’s not necessarily cheaper to shoot digital. But the creative advantages are too big to dismiss. “One of the producers told me he came to the conclusion that [in part because of the number of safety checks required] digital isn’t necessarily less expensive,” says Lasson. “But this film could not have been created on 35mm. It’s not an option. What they were doing with these cameras was groundbreaking cinematography.”

What Color Mill did in post may be groundbreaking, as well. “We custom-built a digital lab, from the ground up, based on the customized workflow,” Cummins explains. “After the project, we dismantled the lab and repurposed the gear. Building such a temp lab is a relatively new concept in production. This leads me to believe that, as more productions go digital, post and lab services will go mobile.”

Given the apparent success of 127 Hours – it’s been a major hit on the festival circuit and is already being talked up for Oscar nominations – Cummins hopes it will help establish Utah as a location state that knows post, too. “Utah’s talent, like Russ, is creatively methodical when it comes to technical problem-solving,” he says. “For practical reasons, these guys up here became early adopters of RED camera technology. They understand file-based workflow as well as anyone else in the business.”

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.

Leave a Reply