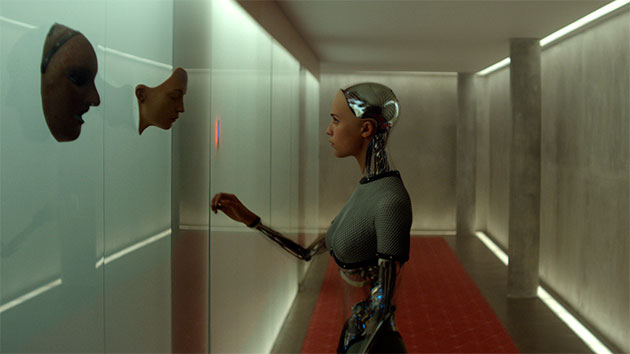

Building a Believable, Transparent Fembot Required Hand-Tracking Actress Alicia Vikander Frame by Frame

First-time director Alex Garland’s quiet, low-budget sci-fi drama Ex Machina received Oscar nominations for visual effects and Garland’s screenplay, five BAFTA nominations (actress, screenplay, visual effects, outstanding debut by a British writer, director or producer, best British film), and numerous film critics awards and nominations. Its estimated $15 million budget gives it the distinction of having had the smallest piggybank of the five films nominated for best visual effects by far. The others drew from $100 million to $200 million moneyboxes. It is also the only film with a first-time director, a first-time overall visual effects supervisor, and the only one of the five films nominated for best visual effects to nominate a CG lead, Mark Ardington of Double Negative.

Double Negative’s Andrew Whitehurst was the overall visual effects supervisor. Whitehurst began his film career as a technical director at Framestore CFC where he worked on the 2004 film Troy, then Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and other films before moving to DNeg for the 2006 film World Trade Center, then Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. He became a visual effects supervisor at DNeg with Skyfall. We asked Whitehurst how the visual effects crew transformed actor Alicia Vikander into a sexy, sentient robot named Ava.

StudioDaily: As you began this project, what did you think would be most difficult?

Andrew Whitehurst: The reason why we have visual effects is always to do something that hasn’t been done before, something you don’t know how to do. I anticipated this film would be difficult because of the constraints, which were mostly because of the budget. The shoot was only six weeks long and we had between 15 and 25 setups every day. There are intimate and delicate moments of dialog between the characters so it was important that the actors and DP [director of photography Rob Hardy] were totally comfortable. Those moments of drama had to work.

So, we tried to keep everything as low key as we could. There was no way anyone could light a greenscreen evenly, so we had to figure out a way to do that without greenscreens. We were careful to shoot clean plates and lighting reference, chrome balls, at the end of every setup, and we were strict about doing that. I thought it would be hard to light the CG components because I knew the sets would have a lot of lighting that we had to match. But, everyone got into a groove, and we captured everything we needed. It [lighting the CG components] wasn’t that bad.

What turned out to be most difficult?

The thing I didn’t anticipate would be so difficult was that we had to body-track by hand every shot of Ava. We couldn’t use motion-capture and I’m not sure it would have been right if it had been feasible. So we had some elements added to the suit’s design — black rubber O-rings with brass studs. They functioned as tracking markers on set and we leveraged tracing those in a computational way.

But because the film was shot using anamorphic lenses including the old crystal express lenses [Cooke Xtal Express], the same ones used on Return of the Jedi, there was no way the software could do the tracking. The lenses model faces beautifully, but beyond the focal plane they do weird stuff. And [Alicia Vikander's] movements are so subtle.

It’s easier to track action. Motion blur gives you places to hide. The hardest thing to body track is the almost imperceptible movement of someone standing still, to copy that sub-pixel movement to match CG with photographed parts. We knew we wouldn’t have a team of animators to finesse it at the end. The raw body track would end up in the film. The most technical R&D happened around designing the rig that the body-tracking artists used to move Ava’s CG body. We were refining the rig right up until delivery. I would never have guessed.

What problems did the anamorphic lenses cause?

There were good aesthetic reasons for choosing the lenses, and they helped us because they have a lovely softness. When we applied that treatment to the CG, it helped it sit into the plates. But the anamorphic lenses are only perfectly unsqueezed at the focal plane. In front or behind, particularly with the older lenses, they warp space vertically. You can get strange stretched highlights that look like footballs on end. Often only parts of Ava are in focus, so we had to warp our geometry for the parts of Ava that weren’t in focus. And when they would slightly zoom in and out, it would change the focus. The computer [tracking] software thinks everything is perfect, so the lenses brought a bunch of tricky issues to us.

It sounds like the crew had to track Ava frame by frame.

Yes, on a frame-by-frame basis. And our average shot length was eight seconds, which is quite long these days. We had one 1800-frame shot that an artist spent three months on, just that.

What was the process?

First, we’d track the camera move so we had a representation in the computer of what the camera was doing and where it was in space. Second, we’d take the CG robot of Ava, overlay it on the plate, match the position of the limbs and torso frame by frame, and keep refining that until we got it as close to perfect as we could manage. Then, we used the lighting reference we took on set to light the CG. At the same time, another artist would paint out areas of Alicia that the CG would replace. So we had Alicia’s floating face, hands, feet, and sometimes the upper torso, and we’d layer in the robotic parts of her. The lighting reference made it feel like she was photographed in the environment, but sometimes the artists added a little extra light here and there to pick out detail and make the shot prettier.

Were the internal CG parts of Ava animated?

We had two elements of extra animation. We baked in the spinning motion of the beautiful gyroscopes to add a bit of interest. We also ran a simulation after the body track so all the muscles would bulge and the cables would have a small amount of shake and jiggle as she moved. It was probably imperceptible to the audience, but those are the subtle things that sell an effect. A couple times we forgot to add it, and when we looked at the motion, it felt staccato, lifeless. So we’d run the simulation again without changing the position of the limbs or the lighting and it felt natural again. Those subtle tweaks helped us bring Ava to life.

Why did you need to develop a new body-tracking rig?

Normally, when you do body-tracking, you’re just tracking the surface. But this character exhibited a full range of movements — kneeling, hunched up, walking, sitting — it needed to be flexible. We needed the skeletal structure and all the muscles doing the right thing with nothing intersecting. It was an incredibly complicated task. We had to deal with things like the way the costume fit on Alicia. It would be different every day because clothes don’t fit the same way every day. Mark Ardington led the building of the rig that enabled the artists to move Ava around. He also built the animation rig to jiggle the cables and bunch the muscles.

Tell us about the other [Oscar] nominees.

I was the overall supervisor and supervised DNeg’s 350 shots of the robots. Milk, led by Sara Bennett, did set extensions, monitors, and Ava’s brain. Paul Norris at DNeg was the 2D supervisor responsible for making sure the plates were cleaned up properly and for the final images. Mark Ardington led the rig-building and worked with the body-tracking artists. He and I started working together making children’s television 15 years ago.

Why do you think your colleagues picked this film to receive an Oscar nomination for best visual effects?

I don’t know what appealed to the voting members. I suppose it has a different vibe. I think at the moment there’s a little bit of a shift in the industry looking at the kinds of films that feature visual effects, from looking only at the summer tentpole blockbusters to more dramatic features. I was talking with a friend, a BAFTA member, who said that for the first time, his picks for best visual effects and best film were all the same titles bar one.

But I hope and imagine that it was that the visual effects were being used to help create a story by creating a character. Work that, although it is up front and center, doesn’t draw attention to itself. I hope that’s what they were looking at, how we supported that. It’s why I get out of bed in the morning.

A different vibe?

It’s rare that a client asks you to be delicate, elegant, and to make things as simple as possible, but that’s the case with most aspects of this film. The camera work, the long gently moving elegant shots. The power of the sequences is in watching them play out. That’s where you get the elegance and power. The people cutting highlight reels for the film had trouble. There were no big bang moments.

The whole film is minimalism, and the visual effects were part of that. Even when I watch the film now, I forget Ava is a visual effect after the first scene. You can’t look past Alicia’s performance, the words she’s given to speak, the prosthetics, the costumes, the way she’s lit. Everyone absolutely pulled together. You have to on a low-budget film. And it became something beyond what we could have imagined. There’s a level of immersion that, to me, is the sign that something magical has happened.

Were you surprised by the nomination?

It was a surprise for everyone involved in the project. It’s still sinking in. It’s rare that a low-budget independent film is considered in the visual-effects category. I don’t think any of us involved with the project expected even to make the long list, and certainly not the nomination. The best thing about the nomination is how excited the crew have been. We were a close-knit little team who worked for a long time. We put heart and soul into the project, never expecting notice or recognition because it’s so small scale. So the team is really, really happy. We loved the work so much.

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.

The guy who did the 1800 frames deserved an Oscar too! Great job guys, congratulations!