It's official: the newest outlet for TV series is Spotify, which today launched a slate of original programs that include both documentary-style shows about music and a Tim-Robbins produced mockumentary series set in the world of aspiring EDM superstars. It's further evidence that just about every online service with a sizable audience wants to get into the game of original content. But is that a good thing?

It's official: the newest outlet for TV series is Spotify, which today launched a slate of original programs that include both documentary-style shows about music and a Tim-Robbins produced mockumentary series set in the world of aspiring EDM superstars. It's further evidence that just about every online service with a sizable audience wants to get into the game of original content. But is that a good thing?

Industry pundits began kicking around the idea of "Peak TV" last year. It's a cautionary term meant to counter the idea that we're living in a new Golden Age of Television by questioning whether greater and greater quantities of quality TV shows can connect with enough viewers to recoup the cost of production.

FX Networks CEO John Landgraf is widely credited with starting the conversation at last year's Television Critics Association summer event, when he asserted that the production of scripted TV series had reached a breaking point. The issue, he said, was not only that it was difficult for viewers to locate worthy shows in the increasingly broad television landscape, but that it was becoming nearly impossible for broadcasters and OTT distributors to bring them successfully to market by building sizable audiences for each one.

"This is simply too much television," Landgraf said, according to The Hollywood Reporter. "My sense is that 2015 or 2016 will represent peak TV In America, and that we'll begin to see declines coming the year after that and beyond."

In a January follow-up with the Los Angeles Times, readers got a sense where at least some of Landgraf's frustation was coming from, when he admitted that FX viewership was down about 13 percent year over year — and called on Netflix to release viewership figures on its own shows. Netflix and Amazon have been tight-lipped when it comes to those numbers, enjoying the critical success of award-winning shows like Netflix's Orange Is the New Black and Amazon's Transparent but declining to specify how many people are watching.

It's easy to see why new players are entering the TV business despite the programming glut. Historically, a hit series — or at least a critical darling — has been a ticket to respectability for newcomers. The letters AMC originally stood for American Movie Classics, and that channel was little more than a Turner Classic Movies wannabe until a program called Mad Men vaulted it into the big leagues. And Amazon Prime was a retail discount club until Transparent put a hot social and political spotlight on the company's previously unloved video-streaming service.

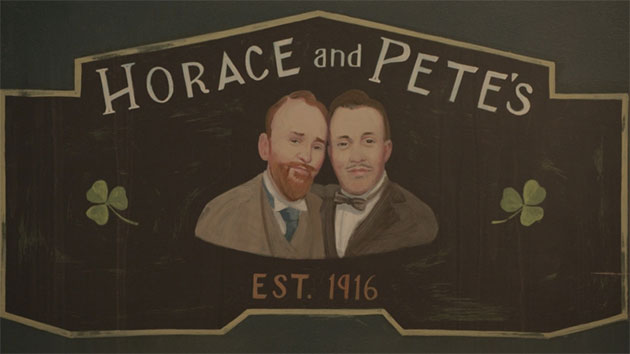

But things get especially interesting when you don't need a broadcast network or even an over-the-top service like Netflix to launch a TV show. Comedian Louis C.K. walked away from his FX series Louie in part to self-produce Horace and Pete, a 10-episode one-hour-plus scripted series that's shot like a multi-camera sitcom. The show is distributed via his own website (if you're enough of a fan of Louis C.K. to want to buy tickets to his performances, or download a $5 stand-up special, odds are you're already on the email list where he gets word out about new projects) for a small per-episode fee, or $31 for the whole series.

Louis C.K. being Louis C.K., he was able to convince real stars to join the cast — Steve Buscemi, Edie Falco, Alan Alda, Jessica Lange. But it's unclear how successful Horace and Pete was as a business venture. Last month, the comedian told Howard Stern that he hadn't made his money back and was in fact "millions of dollars in debt" after funding production. (It couldn't have helped that he kept dropping episodes on Saturdays, historically a slow night for TV-watching.) But that story changed, and he later claimed the show had made money thanks partly to tax incentives. "The tax rebate we're getting from New York State and the amount of sales we have so far have put the show in the black," he told The Hollywood Reporter as he mounted a "balls to the wall" Emmys campaign for the show.

At the Association of Moving Image Archivists' Digital Asset Symposium held in New York City last week, Paul D. Hamm, CEO of OTT video services platform Endavo, was trying to seduce attendees by promising that OTT represents a huge opportunity for content creators as well as anyone sitting on a massive archive of digital video. He noted that OTT distribution adds pay-per-view and/or subscription revenue potential to the traditional advertising model, allowing content owners to hedge their bets against a single strategy.

"Content creators now have the opportunity, using OTT and similar models, to go direct to consumers, and that's a huge change from 10 to 15 years ago," he told attendees. "The business models are changing, and it's a very massive growth market that's starting to develop." He cited The Rugby Channel, which offers live streams, VOD content, archives, and stats to subscribers for a fee of $4.99/month or $49/year, as a niche success story.

So if we are living in an era of peak television, all these new purveyors of OTT content will have to do two things. One, they will have to keep costs down. That might seem obvious, but it's easy to lose sight of your budget if you're trying to "go Hollywood" in a meaningful way. Spotify seems to understand this; its episodes will top out at a mere 15 minutes each, which is one way to get value out of a production budget. And two, they will have to make use of a direct line to their target audience. Louis C.K. had that thanks to his email list, the Rugby Channel has a shot at developing it among American rugby fans who are woefully underserved by traditional sports broadcasting, and Spotify can take advantage of an existing worldwide subscriber based of nearly 30 million users, all of whom have at least a passing interest in music.

And if Spotify can get its users in the habit of watching music-related programming via the service, that opens up new avenues for additional revenue. For instance, it's possible the service could start getting musicians and record labels to finance their own promotional programming in exchange for space on the Spotify video channel, and Spotify exclusives could actually drive new subscriptions — imagine if fans had to have a Spotify subscription rather than an HBO subscription to check out Beyoncé's Twitter-melting Lemonade video album. That would have drawn some eyeballs and, maybe, driven some revenue.

But even if video programming eventually moves from traditional TV channels to an ever-expanding universe of OTT media purveyors, how many eyeballs are available? For a critical discussion of online viewership metrics, see this Gawker explainer, which argues that even wildly successful Internet videos to date have reached an audience that's a mere fraction of primetime viewership. And that brings us back to the real issue of Peak TV — the more fragmented the viewing audience becomes, the harder it is to monetize in a big way. As established companies like FX see their mindshare among TV viewers challenged by a multiplicity of online rivals, they might start to get an idea of how the big three TV networks felt in the 1980s, as widespread adoption of cable television eroded their strangehold on programming. Call it a programming glut or call it "peak TV," it's going to be hard to put that genie back in the bottle.

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.