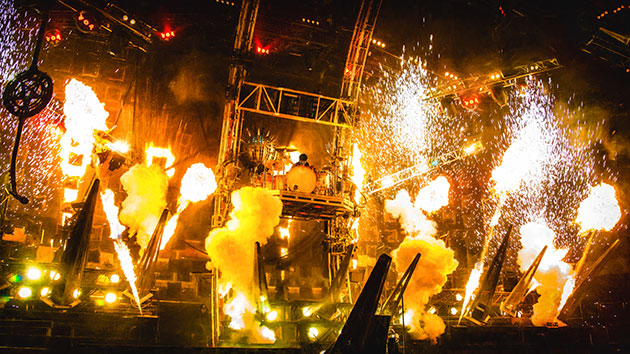

The Band's Last Show Together at Staples Center Was Pure Rock and Roll, Complete with a Spinal Tap Moment

The shoot for Mötley Crüe's farewell concert, captured at the close of a three-night stand at the Staples Center in L.A., was a very rock-and-roll production. Working with the band, director Christian Lamb had a mere four weeks to put the whole project together — a live 4K production destined for screening in cinemas. At that point, the show was already sold out, so even figuring out where to squeeze in the required camera placements was going to be a challenge. "It was overwhelming on so many levels," Lamb tells StudioDaily. "When I sat down with the band in Minneapolis [to discuss the project], it was all about workflow, and the creative, and how we would accomplish everything we wanted to accomplish in an abbreviated amount of time." The resulting concert documentary covers everything from the pre-show load-in, including interviews with the band's road crew, to the full-on performance, with a Phantom camera capturing key moments on stage in super-slo-mo. (It also captures a great moment in bad timing, as drummer Tommy Lee's celebrated Crüe roller-coaster rig stalled out, mid-show.) We talked to Lamb about shooting and cutting Mötley Crüe: The End.

StudioDaily: What cameras did you shoot with, and how many did you have?

Christian Lamb: I had 13 Sony F55s and one Phantom for my high-speed shots. I had shot a series of stills myself on one of the scouts when I watched the show, and on the first night, December 28, I was able to walk with the Phantom DP and get very specific angles throughout the set. he was untethered and I wasn't going to be able to see him during the shoot while I was on the TV truck, so I wanted to make sure he got the specifics of what I was looking for. He had a checklist and went through all of those things. When I got to go through those shots, it was a gold mine.

How many nights did you actually shoot?

December 30 and 31 were the actual multi-camera live performance with the TV truck and 13 cameras running simultaneously. On the 28th, I filmed the load-in, so much of what you see in the five-minute intro is from the 28th.

Did you use footage from both nights freely, or did you privilege footage from the final show on the 31st?

When we went in to edit, the 31st definitely served as the backbone of the entire performance. I was insistent, of course, that the band wear exactly the same thing both nights — even if it was a bandana or accessory, I wanted to make sure it was perfect from night to night. But on the 30th I had totally different camera positions from the 31st. I wanted to maximize my coverage. We had two different camera plots, so it's definitely a mix of the two nights, but leaning more heavily on the 31st. It was challenging in that respect. When we came in, there were very few seat kills, so when we made camera plots for Staples, I had to wedge the positions in where I could get them, including a 50-foot Technocrane.

You had a 50-foot Technocrane inside a sold-out Staples Center?

I had to shoehorn it in. It had a postage-stamp footprint.

That must have been impressive. Were you able to get a good live edit during the show, or did the edit come together in post?

We had a traditional framework on the truck. I had an AD and a TD. Because the ISOs were primary to what we were doing, my focus was absolutely on getting every single composition right — making sure the cameras were in the right place. My TD did a line cut live, so we came away from the show and we had that, and it facilitates everything when it comes to post. When you have the proper line cut, you can lay on top of that — but overall my eyes were entirely on the ISOs, not the pacing of the cut.

What was your editing room like?

We had two parallel cuts in Adobe Premiere Pro. We essentially had to find a way to manage everything and be as efficient as we possibly could, so when I got back from a tiny little vacation I went to Sunset Edit in Hollywood, where I knew they had enough associate editors to rifle through this amount of footage. It's a Mac-based edit house. Both offline and online bays utilize the trash-can Mac Pros. We had 20 TB of raw 23.976 footage and, because we had two editors working simultaneously, transcodes were mirrored on two 12 TB RAIDed Thunderbolt drives. We had two primary editors with two assistant editors as well as an online editor. Our colorist graded in Resolve, and then we onlined the entire project back in Premiere.

When we got in there, the idea was to devote one room to the multicamera live concert and one to the narrative and documentary material. We started with selects in both rooms and just kept building, and I was running from suite to suite. We spent the better part of four weeks, 12 hours a day without a day off. editing. Our goal was to knock out two to three songs a day and then just keep doing revisions.

Are you a happy longtime Premiere Pro user, or is that something you switched to recently?

I was an editor in a past life, when I used to work on an offline system with two 3/4-inch decks and a Mitsubishi black-and-white printer. I was editing longforms for Warner Bros. records, and that gave me a foundation for what I do now. I eventually progressed into nonlinear editing, using Lightworks at one point, along with Avid and Final Cut Pro. Probably about five or six years ago, I started exclusively using Premiere. Whether I was working on my laptop or on a documentary, music video, or multicam shoot, I was gravitating toward it. As far as my own editing goes, I think it's the most intuitive, so it became the norm. I have edited some projects in the past in Avid on multicam, but the more I familiarized myself with the way the timelines work in Premiere, the more it became second nature.

How do you plan in advance how you're going to tell the "story" in terms of the musical performances?

Artists tend to build the concerts in acts, and whether it's very theatrical, like Madonna, or rock and roll, like Mötley Crüe, musicans are aware of pacing. They're not going to stack five ballads in a row and then be doing hard rock until the end. I admired the way Mötley Crüe had built their set. It was very organic, with peaks and valleys as we went, and I wanted to stick to exactly that.

I guess I'm really asking about how you plot out the moments you really need to catch given the setlist. Do you say, "OK, we need to make sure we're here when Vince hits this emotional note during 'Home Sweet Home', and how difficult is it to plan that effectively?

In terms of camera scripting, we had a good plan of what we were going to do for each song. Whether you're talking about the editorial pacing or the actual cinematography of it, the songs have choruses and verses, and some songs you film in a more intimate way. Every song is its own character in that sense.

How did you know what the band would be doing? You didn't have time to rehearse them for the shoot, did you?

No, I didn't have the luxury of camera blocking time. I saw the show in Minneapolis and shot a few stills, and then I saw it on the 28th at Staples Center. It wasn't as much as I would have liked to see, but I felt like I knew the show, and the band's movements, well enough to piece it together and be in the right places.

Did you have any other music films in mind as a template?

Nothing specific. I think you take something from everything you see. It becomes a combination of all of the creative ideas you have flowing. Of course there are films that have inspired me in the past — The Last Waltz, Pink Floyd Live at Pompeii, Sam Bayer's Green Day film Bullet in a Bible. Different aspects of all these different films play into it, but there's no specific plan.

I have to ask you about that moment when Tommy's drum kit stalls out on the Crüecifly roller coaster. It's kind of a Spinal Tap moment.

It was real! The reason This Is Spinal Tap resonates is because Rob Reiner toured. He wrote that script out of things that really happened on tours. That's the great thing about rock and roll. These things happen and there is, eventually, an element of levity. In the moment, it was a crisis, and there was a knee-jerk reaction afterward where everyone from top to bottom — especially Tommy — said "Thank god we filmed on the 30th!" In my mind, I was never headed in that direction. I saw it trending on Twitter that night, and then the story took off. So I pitched my idea to management. I said, "I think we need to be truthful about this. The cat's well out of the bag. One YouTube video had 350,000 hits. We would look like liars if we showed this thing working flawlessly." So we had a conference call with Tommy and I pitched it to him. I said, "We'll look like assholes if we try to make this thing what it wasn't. We're not going to leave you upside down for eight minutes, but we need to allude to what happened." He said, "Show me your idea in an edit," so I made it like a 60-second moment. It was part of the storytelling, and it became part of the fabric of the show.

What was your final delivery? Did you finish it in 4K?

Our deliverables included native 23.976 and 24 and 29.97 conversions in 4K and 2K. We were shooting for 4K, knowing there was the potential for a big-screen release with Eagle Rock, so we had to set the bar pretty high. If you have the ability, it's obviously best to film in 4K.

Does it ever bog you down to be working at 4K when you're trying to just get a project finished on deadline?

It can. It becomes a bigger pipeline when you need to do something of that nature. But the creative came first, and we just had to make it work technically along with all the other aspects. We were dealing with a tremendous amount of footage. It might have been easier to do that in a 1080 world — but we decided to go to a higher level.

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.

Leave a Reply