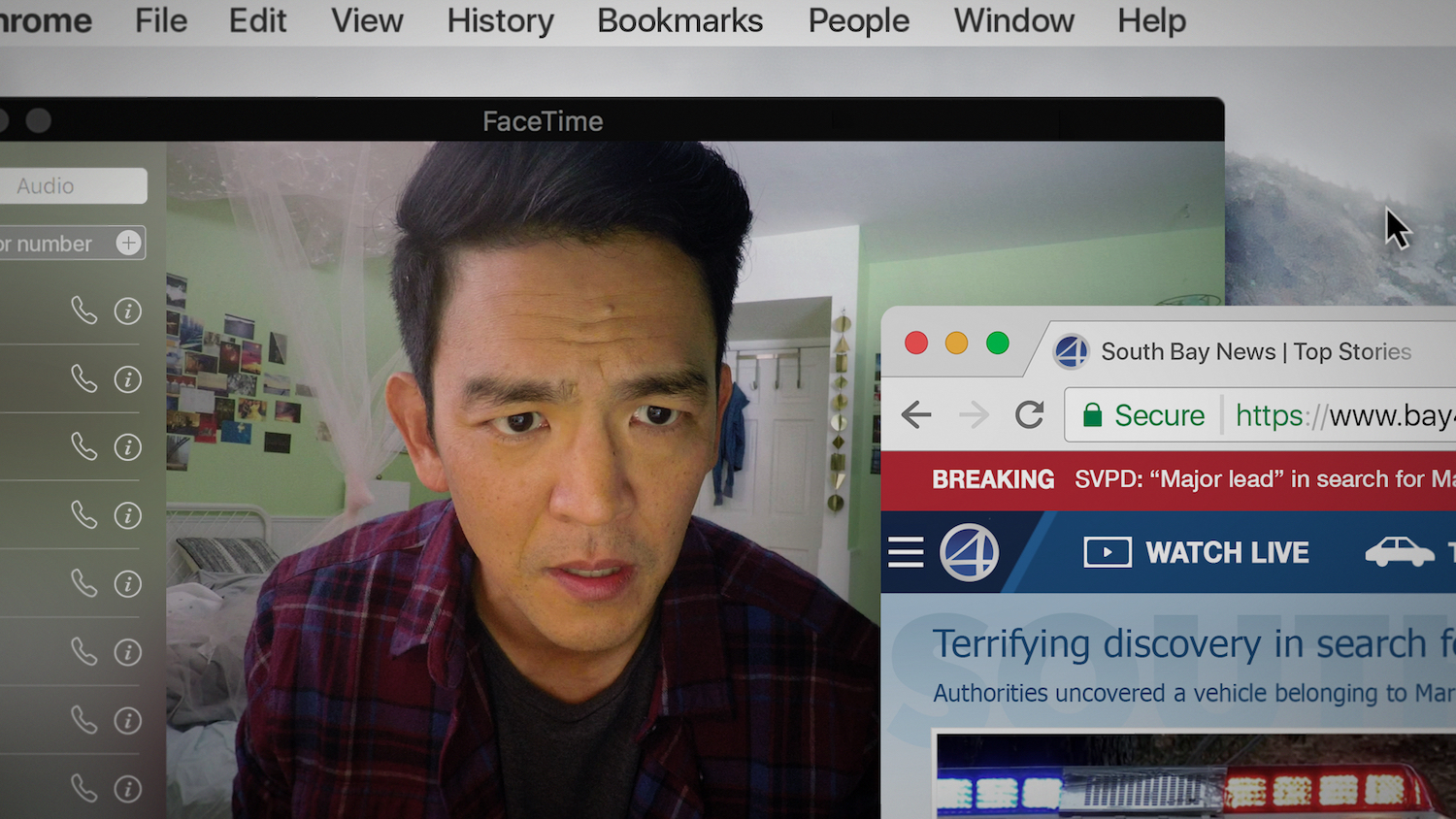

Searching, a film told entirely through computer and device screens, is not your average thriller. It’s much more personal — and terrifyingly plausible in a society obsessed with communicating digitally. Based on the social media-driven film language and technology that producer Timur Bekmambetov has coined Screenlife, it follows a bereft father (John Cho) searching for his missing teenage daughter through the parallel and divergent rabbit holes of her life online. Rolling Stone‘s Peter Travers called the movie “a technical marvel with a beating heart at its core” and it’s been an under-the-radar hit with audiences in the U.S. and abroad since its release.

Cinematographer Juan Sebastian Baron met the film’s director Aneesh Chaganty when the two were randomly paired for a class project in film school at USC. Chaganty is no stranger to small screens and first-person POVs. His debut commercial effort, “Seeds,” the first ad made entirely with Google Glass, landed him a job at Google Creative Lab in New York making short films. Baron has long been Chaganty’s cinematic sounding board, so when Chaganty showed him the feature-length dramatic script he had written with Sev Ohanian, the gaffer and DP (The House on Pine Street, Don Quixote) jumped at the chance to work with his classmate again.

We asked Baron how he adapted his traditional cinematography training to this unusual project and what he did to squeeze the highest production values out of the stylistic and budget constraints the team faced on set.

StudioDaily: Were you wary of taking on such a high-concept project with a pretty limiting framing device?

Juan Sebastian Baron: When Aneesh first showed me the script and asked me to shoot it, I thought it just made a lot of sense, since we had worked together in the past. Sure, at first, I would normally be very hesitant and even a little skeptical that you could pull something like this off. And even though the project had Aneesh and Sev, as well as Timur, behind it, I definitely had some skepticism about whether we would be able to make something compelling and coherent and interesting enough for someone to sit through an hour and a half of it. But knowing Aneesh, who has always been a very ambitious guy and seeing what he had created while at Google, I felt very confident that he knew exactly what he was doing and would be able to take all of the traditional filmmaking skill set and apply it to this new medium.

What do you typically shoot with and how did the camera kit differ for Searching?

I’ve shot pretty much everything from shorts to TV to features on an Alexa or Red, and I’m most comfortable shooting in either of those platforms. Early on for this project we had a lot of discussions about how to shoot it. Do we use a traditional camera and then degrade the different looks we wanted in post? But very quickly we came to the realization that because the script is so organic and authentic and based on the real UI of a computer and handheld devices, we knew we needed to match that effect with the photography. So to shoot this as close to real as possible that meant the camera kit became GoPros, iPhones, consumer MiniDV cameras, and a Canon 6D. In some cases, we had to make compromises. In an ideal world, I would have used a news camera and a news helicopter to capture all the news footage. But because of our budget constraints, I needed to find a small-sensor digital camera that shot 4K, since we needed to be able to punch into the footage. I wasn’t just looking at a 16×9 frame and wondering if it looked warped. I knew the editors would be punching into the footage, so I had to also ask, what does the texture of the image look like when it’s punched in? It was a very unconventional way to work and it did mean that we ended up doing this entire movie on prosumer and consumer products.

You also had to reflect the passage of time and more than a decade of video and images of the missing daughter.

Yea, those technological changes over the years meant we had to adapt and shoot what the time period depicted demanded, whether a MiniDV, a consumer camcorder with the little servo zoom, [or] a point-and-shoot camera that would make the images blurry and really low-res, but those constrictions helped a lot, because it tied in to the performance of the actors. We could, for example, grab a camcorder that John Cho used years ago and he was able to just pick it up and operate it, giving those scenes real authenticity. It was a difficult decision to make and although it challenged me and was a lot of fun, from my end, it wasn’t always ideal. It just takes you out of your comfort zone of incredible technology on set that we rely on. I was shooting with GoPros on top of a laptop and controlling from an iPad, and we’re juggling 12 different ones that all need their own passwords and batteries.

What was your A camera, then?

Our director Aneesh’s personal iPhone! I mean, no one rents iPhones, so that kind of forced our hand. And it wasn’t in our budget to buy a dedicated iPhone. So you can imagine: he’s using it to do all the things he needs to do, like putting out fires, texting actors, and answering emails, while my camera assistant is running behind him at all times making sure his iPhone is fully charged so we can do a take with it. We discovered some funny things, too. Obviously we have to put the phone in airplane mode when we’re shooting with it so we don’t get a random phone call in the middle of a take. It was tricky. You might have a scene where an actor is talking into their phone, and it’s in selfie mode, so they can see themselves on the screen. Most of them found that very jarring and distracting; you don’t act into a mirror. So we had to tape over the screens. Other times, an actor might inadvertently bump a button during a performance and we’d miss a take. Debra Messing gave an amazing performance in one take but she’d accidentally flipped the screen so the camera was facing in the other direction and we had no way of knowing that until after we were done.

Do you think the approach paid off in the end?

Absolutely, but it was a really unique challenge. As a cinematographer, you spend so many years developing a workflow that you can rely on so you don’t have to worry and can just focus on the creative aspects of a project. This kind of felt like going back to film school in a weird way. We put GoPros on top of the laptops as webcams to simulate the FaceTime sequences, and that allowed us to still have video village and a somewhat traditional workflow. But those are auto-exposure cameras and you can’t control the exposure or the look, so it became a process of learning the black art of tricking the GoPro into making it look like what you wanted. If you put a highlight or a lamp in the shot, the camera would try to expose for that and darken the scene. You end up playing around in a really unconventional way to try to get it to look the way you intend it to.

In what other ways did you manipulate the light when composing your shots?

Going into the prep process for this, we approached it like you would any normal narrative project — you talk about the character arcs and drill down on moments we want to highlight, you figure out what the vibe and mood of each scene, and “how would I light it if I had my traditional workflow”. By doing that first, we were able to adapt it to the various camera technology as we went along. We came up with some very interesting ideas. When you’re sort of restricted on a two-dimensional frame, you get freed up a little bit to come up with something new. Because we couldn’t do much with other lights in the room, we played a lot with the glow coming from the screen. We realized in the first couple of days on set that the light from the screen was a primary element that needed to be modified and shaped as the film goes along. Once we knew that and got more confident, it became more about looking at the frame and just making it feel right. Once we realized it was working, we started to take bigger risks and have a whole scene where it’s lit entirely by the computer screen. As he gets sucked into the search for his daughter, the screen becomes more present and dominant; you can see it in his eyes. And all of that had a huge emotional effect on the story.

What about color?

We played with it throughout and there’s a lot of color symbolism in the movie. But it had to always be a balance, because we wanted it to feel like an authentic computer experience but it’s fundamentally a cinematic experience at the same time.

Debra Messing and John Cho

Elizabeth Kitchens/Sony Pictures

How did you organize and deliver dailies to the editors with all these various formats/frame sizes in play?

Basically, the way we set up the workflow was pretty much the way you would for an animated film: through pre-vis and storyboards. It is similar to a green-screen movie, when so much of the construction was happening in post and the actors were having to pretend that these various screens and interfaces were moving around your performance. We had a mock-up of the film, but it was pretty funny because it’s Aneesh playing every character. So we had references of where a character would be looking and how his eyes would track from one part of the screen to the other, for example. We had a lot of conversations about what worked in these mockups and what didn’t. This was a really rare experience because we had the editors involved in pre-production. That’s something that really only happens in animated movies. But it helped with a lot of other things. Throughout the entire production — which we actually referred to as “asset acquisition,” because it was when we had to grab all these various pieces that we needed to assemble the whole — we were able to go back to the mockup for guidance and to make key decisions.

Your schedule must have been a bit unique, too.

Yea, I was on for about one month of pre-production and we shot for 14 days, and of course went on to a few additional pick-up days later on. The pick-ups were mostly because as they were editing the final film a lot of individual pieces started to pop up that we needed individual assets for.

Like a puzzle.

It really was. This film was probably the most challenging thing I’ve done from an abstract, organizational, logistical standpoint. It felt like we were approaching film from a totally new point of view. But at the end of the day, we really relied on a lot of the basics. Early on, we had conversations about whether or not we should have a script supervisor and a shot list and theme numbers, and it turned out to make the most sense. Everybody still needed a common set of rules to work within and reference. We had all the same challenges that you would have on a normal film, from hair and makeup to props and set decor continuity. We also shot a lot on sound stages and had to light them from scratch. And many of the exterior locations were fabricated. There were a lot of times we felt we were making a regular movie. But by the time we starting shooting it, we were very aware it was not a regular movie and we were all outside of our comfort zones.

Did the talent all buy in to the concept from the start?

Aneesh definitely did an amazing job of selling them on the vision and how he wanted to make the film. He’s such a universal filmmaker and the story is so classic and grounded. He’s also just such an incredibly passionate guy that you can’t help but believe him. I think when they all actually sat down in front of our GoPro-rigged laptops, I can almost guarantee that they each had a moment of doubt and wondered what they got themselves into! But once we got into the rhythm of it, they all fell right into a traditional acting approach. For our younger actors, it so easy. They already live fully in that world. But Debra Messing has a huge presence on social media, so she’s very familiar with digital life and fell right into it, too. And of course, John did such an amazing job of being very present in that role, and he understood how subtle and finely tuned his emotions had to be when his face was right up against the computer and he needed to still react to something on the screen. Acting for a wide shot and for a closeup are very different experiences.

Do you think this is the start of a new era of small screen-focused filmmaking?

It almost feels inevitable that we start making more movies like this. There are so many things about our day-to-day lives that have so much drama and comedy and still all take place on computers. It’s about time [that] cinema — and not just another corridor of the computer like YouTube — is able to represent that fully and recreate the world we inhabit.

Searching is currently in U.S. theatrical release. It arrives on streaming platforms November 13 and on Blu-ray and DVD November 27.

Crafts: Shooting

Sections: Creativity

Topics: Article Category Project/Case study Canon 6D GoPro Hero3 iPhone

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.