Why Rear Projection with LED Screens Is Changing the Way Movies Work in Production and Post

In Universal Pictures’ First Man, we follow astronaut Neil Armstrong from 1961 until he famously takes his first steps on the moon. The innovative visual effects put us inside the shaky cockpits. We see the light from the cosmos out the small windows and reflected on visors.

Oscar-winning director Damien Chazelle teamed up again with actor Ryan Gosling from La La Land for this film, with Gosling playing Armstrong and Claire Foy as his wife Janet. Paul Lambert, who received an Oscar and a BAFTA award last year for supervising effects in Blade Runner 2049, managed the visual effects.

First Man has received four Oscar nominations — for sound editing, sound mixing, production design, and visual effects — and seven BAFTA nominations — for cinematography, editing, adapted screenplay, special visual effects, sound, production design, and best supporting actress.

Miniature Effects Supervisor Ian Hunter from New Deal Studios, Digital Effects Supervisor Tristan Myles from Dneg, Special Effects Supervisor J.D. Schwalm, and Visual Effects Supervisor Paul Lambert received the Oscar and BAFTA nominations. Those four plus Kevin Elam (associate producer) received the VES award for outstanding supporting visual effects in a photoreal feature.

According to IMDb, First Man had an estimated budget of $60 million and earned more than $100 million at the worldwide box office. The review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes gave it an 88% approval rating.

We spoke with Paul Lambert about the film. In addition to three nominations for First Man and his Oscar, BAFTA award, and VES nomination last year for his work on Blade Runner 2049, he has received a VES award for compositing The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and additional VES nominations for compositing a Kia commercial and Tron: Legacy.

We’ve interviewed all five Oscar-nominated VFX supervisors. Click here to read the rest of the Q&As.

StudioDaily: Why do you think your peers voted to give Oscar nominations for best visual effects to First Man?

Paul Lambert: Each year the work gets better and better. The amount of work — the character work — done on some of these movies is phenomenal. It takes hundreds and hundreds of people. But this filmmaker wanted to get as much on set as possible. And I’m a big believer in that, as well. For me, personally, there was a big change in how we did things for this project, and I think different aspects of our work resonated with my peers in different disciplines. First Man used a wide variety of techniques, but in a modern way. At the core, we wanted to use the best technique to create something with the most realistic look.

How did Director Damien Chazelle’s brief change your approach?

We tried to keep to this philosophy: What would be the best technique for a particular shot? We spent three or four months just discussing ideas, trying to work out a practical approach to the visual effects, backed up by the latest technology. We relied heavily on special effects. We used archival footage. We used visual effects to enhance locations rather than putting actors in green or blue environments. We used miniatures and added digital components to them when required. We did more work in pre-production and in the shooting than we expected. The base of a lot of it was traditional rear-projection and miniatures, but the cutting edge was rear-screen projection using LED screens.

Why did you use LED screens?

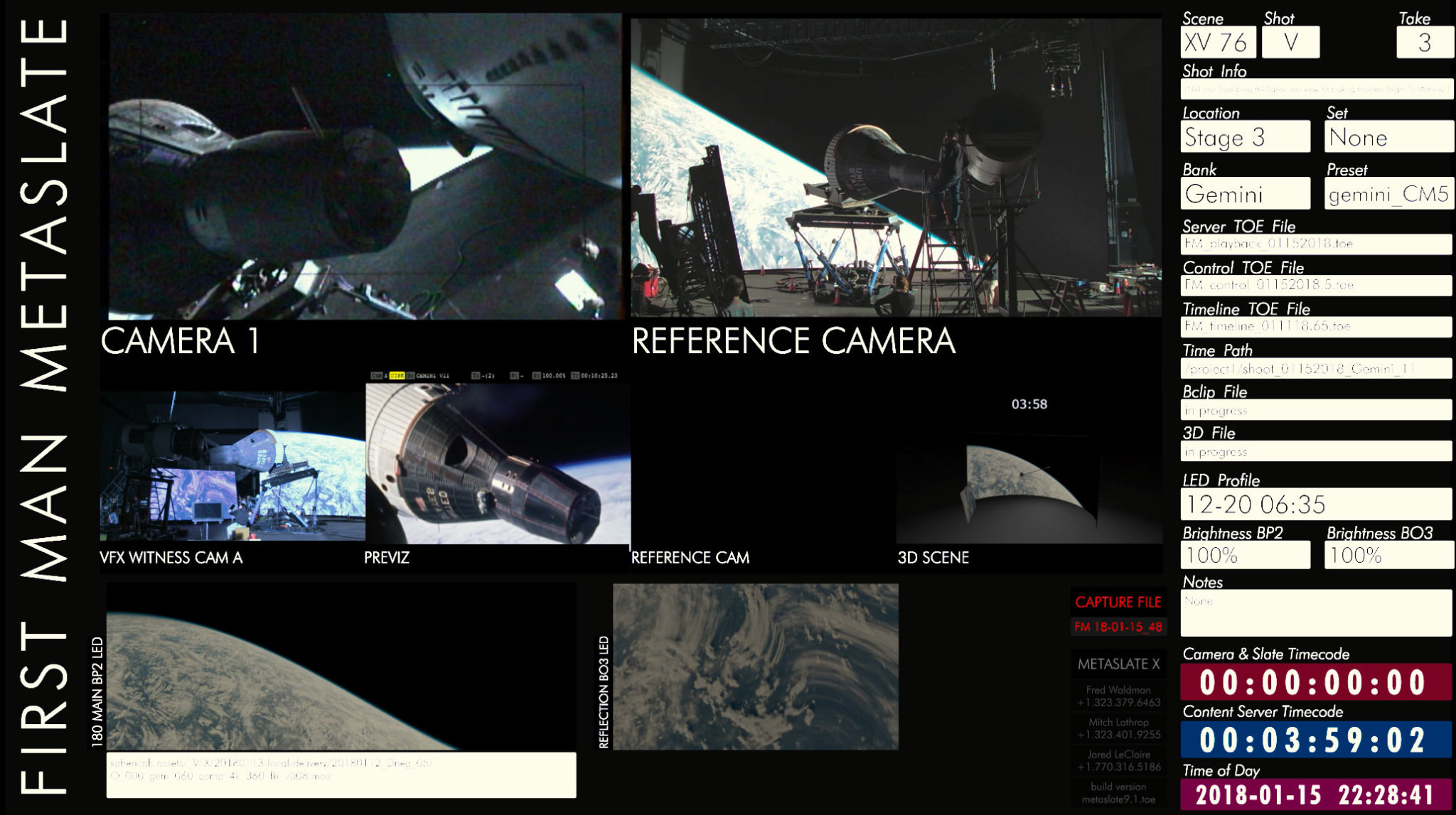

Even with a huge practical approach, we always knew we would have to have CG. But we wanted to do it in a way the filmmakers could be part of it. After a shoot, the DP is usually no longer involved, and the art director is no longer involved. We wanted to use all the talent from the people on set, so we played around with the idea what if we had content on a screen.

I believe LED technology has come a long way, so we made a rudimentary set up with a CG moon and clouds. We set up a small screen, put that content on the screen, and used film production cameras — 16mm, 35mm, and Imax. Having the CG on the LED screen meant that it passed through the film cameras, which gave it film grain and patina without having to pass it through comp to match the grain. It was actually coming through on the dailies. We knew we were on to something. So, we did a bigger test on a bigger screen.

What size did you end up with?

We had a 180 degree screen 35 feet tall and 60 feet wide. Imagine 1200 LED TV screens.

Actor Ryan Gosling saw the same thing out his capsule window while shooting that the audience saw in the final film.

How many shots did you have and how many did you produce for the LED screen?

We had 615 visual effects shots, plus a lot more than that in terms of visual effects that were not touched in post. We created over 90 minutes of footage for the LED screen. We don’t have 90 minutes in the movie — there were various takes. Damien didn’t want to be constrained by cuts while shooting; he wanted to run the camera like filming a play. So we spent a lot of additional time in preproduction and during the shoot trying to produce the images.

For example, when Neil Armstrong [Gosling] is flying on the X-15 and bounces off the atmosphere, Damien wanted one entire clip so he could work at any point with Ryan. What they saw was the actual content. Otherwise when a horizon would appear, Ryan would have to pretend. But here, he saw the horizon. And, because it was on the LED screen, he was able to keep his helmet on, so we got the reflection of the horizon in the visor and in his eye. What’s reflecting is actually the visual effects. But because it wasn’t touched in post, they don’t count it in the shot total.

Also, when the astronauts are blasting off in the rocket, we see them inside the capsule and they all have reflections on their helmets and on the dials. Those aren’t counted as post work because they were shot in camera. There wasn’t an additional cost to the filmmakers for post vfx.

The rear-projected VFX were reflected live on set in Gosling’s helmet visor.

That puts a different slant on what constitutes visual effects, doesn’t it?

It’s a complete paradigm shift as to where the money is spent on the work. We spent money in pre-production knowing we wouldn’t spend it in post. The 615 shots are only the ones we worked on in post. We don’t have a number for all the shots where the visors or the eyes or dials catch reflections from the CG on the LED screens. There are shots we wouldn’t have turned over to post. I know how tricky it would have been in post to create a CG eyeball with the correct surface to get the correct reflection. It’s complex and quite frankly, we’d ask, “Do you really need it? Do you want to spend money on that?” But it’s another little piece that makes the whole thing believable. And, having an entire sequence influenced this way adds another layer of believability.

Speaking of believability, I’ve read you had access to archival footage from NASA.

Every launch at NASA had scientific engineering cameras to film different aspects of the launch in case something went wrong. Apart from the Apollo 1 catastrophe, which wasn’t a launch, nothing went wrong. All that film was stored in film cans and we got access to it. Some was fairly decent, but all of it required cleanup. It was on 70mm stock, so our [associate producer] Kevin Elam spent months looking for a facility to do a scan. Finally, we found FilmLight in London. They were developing a scanner that doesn’t use sprockets.

Damien wasn’t interested in having new camera moves. He wanted visuals people had seen versions of. As we pulled more and more reference, I thought, OK, we can do something here. I was quite happy.

Once we had that footage and other 35mm footage, we came up with techniques to take out all the scratches and artifacts, compress the frames to speed it up, and in doing so added some motion blur. So it looked as if it had been shot at 24 frames per second. Where there were areas that weren’t sharp enough we would use CG or matte paintings. Also, because engineering cameras were basically square, we cut the top and bottom slightly and extended the sides.

Our goal was to clean it up and make it pristine so when we cut it back into the edit it would pop out as way too clean. At that point we could degrade the footage to fit within the production 16 and 35 surrounding it. At no point could the audience believe we were using archival footage — it would have taken them out of the story.

Give me an example where you actually used the cleaned-up archival footage in the film.

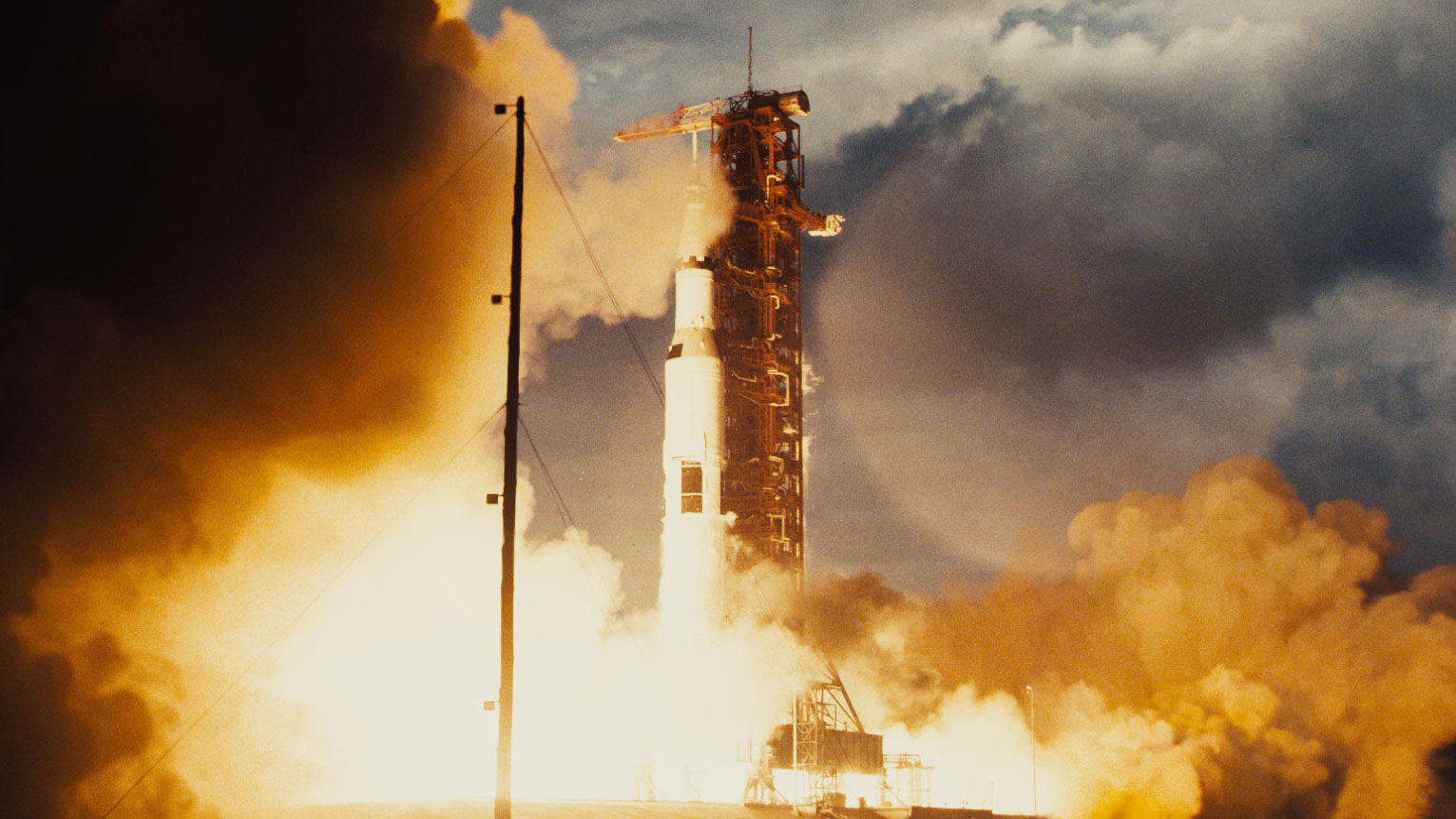

There’s a wide on the Saturn V igniting where you see plumes of fire. That’s from original footage of the Apollo 14, cleaned up, stabilized, and extended out. It worked really well. Throughout that sequence we also either replaced archival footage with CG or put it on top. We were planning to recreate the sequence with miniatures, but the more reference we pulled, the more we could use the archival footage.

You did use miniatures, though?

We built a full-size capsule. We also had an 80%-sized version of the Gemini. Our philosophy was if you’re going to be close to one of the mounted crafts, we would use the full or 80 percent size. If it was mid-sized, we used the 1/6 scale. Farther out, we used CG. We tried to stick to that.

Ian Hunter’s crew made those versions and also a 1/30 scale Saturn V that was about 14 feet tall. You see that when Ryan [Gosling] looks up to the rocket while standing outside the building. You see the 1/6 scale when we do the docking, when separating from the CSM to pull the LEM out.

CG was used for wide shots of the spacecraft, but closer shots used scale models.

Were the interiors set pieces?

They were all full scale. We also had to build other versions to pull out certain sections. In a shot where you see the astronauts weightless, we had them attached to wires. One-third of the set above them is removed and replaced with CG so the wires could travel down. The astronauts travel from one capsule to another and spin around, so we put two different sets together and matched the takes. It was a very organized approach.

Was NASA involved in the project?

We had NASA advisers throughout the filming and through post. They were very specific about the dials. All the dials in the capsule and the X-15 were controllable. We didn’t add them in post. Damien wanted the dials to be functional and that’s exactly what we had. It added believability.

There is a lot of shaking going on during lift-off and a few other times. Was that camera shake? Added in post?

It was nearly all done in camera. Usually, we don’t do that on set; we add it in post. But shake is actually tricky. Film cameras have certain characteristics and in post, although camera shake is supposed to be easy, to get the actual look is tricky if you’re just shaking the camera.

So we actually shook the gimbal and got everything and everybody inside shaking. The actors would spend the entire day being shook. At the end of the day, they weren’t the same color as when they started in the morning. Of course, that made tracking harder, but it doesn’t make it impossible. And the result is way better.

Is the surface of the moon CG?

We had a couple versions of the moon — distant and more specific. We had five acres of a quarry on the outskirts of Atlanta dressed to look like the landing area. There was a 200K movie light source, but it didn’t have enough spread, so we had to spread it out more in post. This sequence was in Imax, so it had massive, 6K resolution. We had sun reflectors on the helmet to catch that light, but it also reflected the crew and all their tents. We cleaned that up and the cranes in the distance.

For the approach, we had two CG versions, distant and more specific. The moon has been mapped many times and all that data is available. But we added a bit of Hollywood magic with the big crater to make it look more perilous visually. The archival footage makes it look easy, but it’s not and wasn’t, so we played it up a little bit.

What was it like working with a director who had never directed a visual effects-heavy film?

Damien had a few visual effects in La La Land, but he had never been exposed to a visual effects project at this scale. I believe that not having been through that process, he asked new questions. “Why can’t we do it this way?” We kinda went with it. Damien’s having not gone through a more traditional effects heavy movie gave this one a fresh way of doing things that I’ll stick to in future projects. Some of that is a change of mindset.

How has your mindset changed?

Whenever people talk about doing content for LED screens, the question comes up, “What if the director changes his mind later?” I had to stop and think for a second. The director makes decisions on a shoot every single second of the day. He likes this prop, likes that tree. He’s making decisions every day about what he wants on the set. Visionary directors have in their head how the movie will look and they make that decision in the shoot. If they want to change it later, that’s an additional cost.

We seem to have gotten to the point where we do multiple versions in post. Having the background on an LED screen is a different paradigm. It’s not like having green or blue screens where 167 ideas for the background can come up in post because it wasn’t thought out in the beginning. [Instead,] it’s like taking the shot cost from post and concentrating it on the shoot.

Other productions will take this idea further. It’s the next step up from green-screen and blue-screen because it provides an interactive environment, and if you have backgrounds with various lights it’s better than a long comp process.

What was the hardest part of making this movie?

It was a big-budget movie with a low budget. But we had exceptionally talented heads of departments all focused on making the most believable movie from the 1960s.

And the best part?

I love this movie. It’s so inspirational. On the last day of the shoot, everyone is tired from working long hours. But Damien and [editor] Tom Cross put together a montage with snippets from all the sequences and cut it to [Sir Edmund] Hillary’s speech. It was so moving. I was almost sent to tears. OK, this is why we’ve worked so hard. I knew we had created something special.

What did you learn?

Even though it gave me gray hair, the LED screen is my best friend.

You’re working on Dune next with Denis Villeneuve, who directed Blade Runner 2049. What can you tell us about this project?

Let’s just say that it’s going to be a good one.

Crafts: VFX/Animation

Sections: Creativity

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.