How VFX Supe Thomas J. Smith Became an On-Set Referee

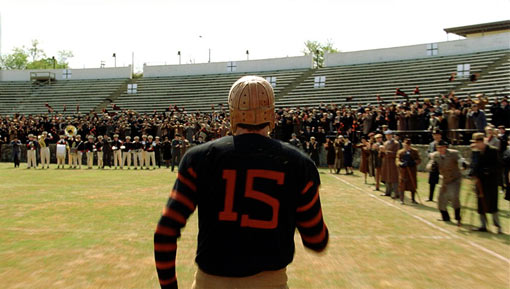

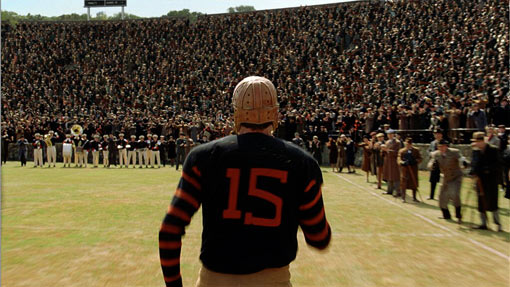

To make that possible, visual-effects artists at CIS Hollywood worked with Clooney and production designer Jim Bissell to turn a junior-high-school football field in Boiling Springs, SC, a middle-school football field in Travelers Rest, SC, and Memorial Stadium in Charlotte, NC into ever-larger stadiums that they filled with crowds of digital people. Visual-effects supervisor Thomas J. Smith led a crew of approximately 40 artists who used Maya, PhotoModeler, RealViz, Shake, Silhouette, Massive, and RenderMan over approximately five months to accomplish the triple-play.

Smith had met Clooney while working on Ocean’s 11, one of 14 features that CIS worked on during 2007. “We showed him the work we had just finished for We Are Marshall, which was our first football film,” Smith says. The film was the first for which CIS had created football stadiums and digital crowds, and, based on what they had learned on that film, Smith suggested a template Clooney might use for Leatherheads.

“We explained that our crowds work well to 35 or 40 feet, but when we start seeing the people sharp and clear, he’d need 200 or 300 people to cover the action,” Smith says. “That was the agreement we came to. You have to put a lot of time and energy into digital characters to have them look photoreal, so we all knew from day one that the digital crowds would work only to a certain point.”

Thus, when Clooney filmed a football game, Smith became an on-set referee, flagging penalties on instant replays. “We could see what was in focus on the video playback and could tell when they were in what we called the ‘no-fly’ zone,” he says. “So we’d tell the crew that they had to be careful, that our crowds might not hold up.”

With the help of the ADs, Smith moved between 300 and 500 extras around the lower levels of the stadiums as the camera changed to keep real people in the foreground. The extras also provided good reference for the digital crowds CIS would create later.

Director of photography Newton Thomas Sigel, who had shot Superman Returns, helped make sure Smith and the CIS crew had the camera information they needed. “There was no way we could have used green-screen for something as large as a football stadium,” Smith says. “So we let the filmmakers shoot their movie and then rotoscoped everyone out of the foreground. They shot the football games with three cameras and had a Steadicam standing by, so they had a lot of coverage.”

Smith’s on-set coaching extended to keeping other potential issues from penalizing the post-production process as well. He noticed, for example, a shot in which Zellweger’s position in front of a partially filled stadium could play havoc later. “Her blond hairs were wisping around in the wind, and the camera was dollying, so I threw the flag up,” he says. “It would have been difficult to rotoscope her hair.” The solution? Zellweger wore a hat.

For camera tracking, CIS relied on Yannix Technologies, but the studio handled rotoscoping largely in-house, with eight artists using Shake and Silhouette to lift actors from plates so they could insert stadiums and crowds behind. Simultaneously, modelers at CIS began building the stadiums and the crowd-simulation team began creating digital fans.

Art director Jim Bissell had worked in Sketch Up to design stadium extensions for the production, and the crew began with those files as they started work on models in Maya. “We double-checked and measured the actual stadiums to be accurate so that our 3D overlays would fit precisely, but the files Jim gave us were helpful tools for getting started,” Smith says.

In addition, CIS photographed the stadiums on location from multiple angles and used PhotoModeler to derive 3D models that, once in Maya, gave modelers a starting point for building the 3D extensions. The grand finale game, which the production crew shot in Charlotte, takes place in Chicago. For that game, CIS artists put 30,000 fans in a stadium that they had extended in 3D, with a matte painting of the Chicago skyline behind.

For the crowds, the team motion-captured an actor playing the part of people watching a game – sitting, watching, talking, acting excited, and so forth – so that those motion cycles could drive Massive agents of various sizes representing men, women and children. By categorizing the animation by levels of excitement, the studio could direct Massive to cause a specified percentage of the crowd to jump up and down, act moderately excited, or simply move back and forth. Reel FX helped CIS set up the system.

“With Massive software, you need to build your own pipeline to take advantage of all the benefits, so we had Reel FX help us with some internal pipeline issues and some of the animation,” Smith says. Massive put the agents into the live-action and 3D bleachers.

To costume the agents, the studio photographed the extras in their period clothing. “We grabbed four-pose photographs,” Smith says. “We brought those photographs in and applied them as painted textures to 3D models.” Because the crew was confident that the digital fans would not be seen close-up, they didn’t need to do cloth simulation. Assigning the approximately 50 textures randomly to the digital fans helped keep patterns from repeating.

“We had the ability to change colors when we rendered the shots in RenderMan,” Smith says. “And we also had the ability to change numerous things within a scene using hold-out mattes. So we could alter colors in composite. With 50 or so textures, the odds are against getting everything right the first time out of RenderMan, so we stayed flexible.”

In the film, CIS’s artful effects blend into the background as they should, but the success of the project depended on planning as well as artistry, and on the cooperation among the production and post-production crews. “It was such a pleasure working with George Clooney and [producer] Grant Heslov because they always welcomed our input, which doesn’t always happen in the visual-effects arena,” Smith says.

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.

Leave a Reply