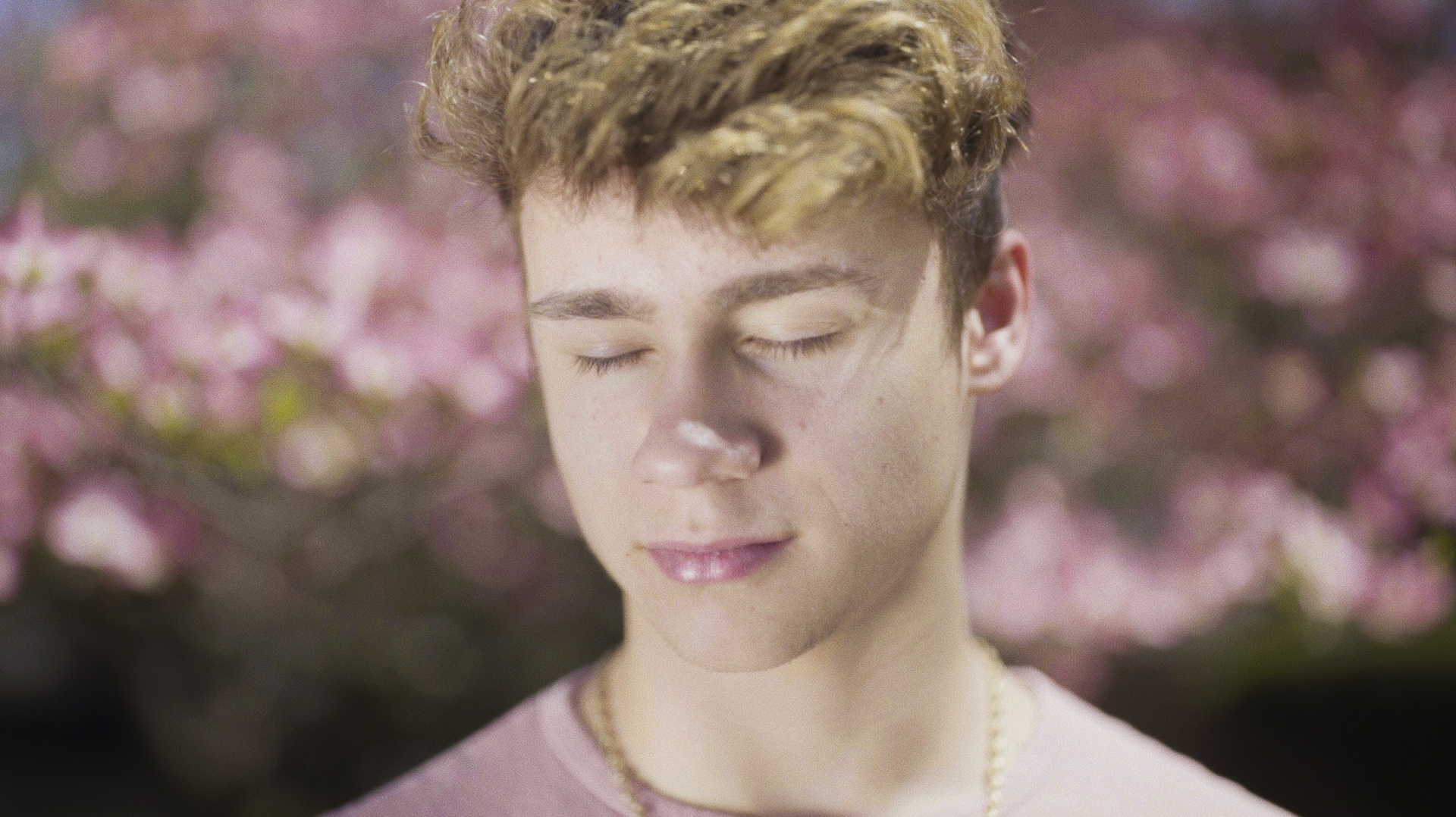

Liza Mandelup’s first feature, Jawline, takes a critical but empathetic look at teenager Austyn Tester, who is trying to escape poverty and life in rural Tennessee by becoming a celebrity broadcasting on the platform YouNow. She cross-cuts his story with that of Michael Weist, a slightly older man running a management firm for young media personalities in L.A.

The culture is moving so fast that reality TV seems as distant to the kids depicted here as Frank Sinatra did to me when I was their age. But there’s something eternal about fans finding real solace from the work of people trying to escape poverty and a brutal class divide. Jawline offers an up-to-the-minute dispatch on the false promise of fame via social media, but Austyn is probably right that it’s his only chance of escaping a life of menial jobs.

Mandelup has explored contemporary youth in a series of shorts leading up to Jawline. (You can see them on her website.) It opens in New York and Los Angeles — and begins streaming on Hulu — today.

StudioDaily: The world you depict, both in Jawline and “Fangirl,” is very strictly divided into male creators and female fans. Before making Jawline, did you look into female YouTubers and influencers and male fans before settling on that subject?

Liza Mandelup: My interest came from realizing there was a market in capitalizing on teenage girls’ insecurities. There was a full business built around the fact that girls felt vulnerable and unloved around this time in their life, especially middle school and high school. The social media influencers we see in the film are leaning into that and making money off it. There’s all kinds of dynamics that exist in the world. I was interested in the specific market of desire.

How did you approach shooting off computer and phone screens?

It was difficult, because this world is not naturally cinematic. My approach was to film as much as possible the moments before and after. I was more interested in what happens when you’re no longer acting like the character you’ve created online. The film mostly takes place in the spaces in between screen time. I think that was the world I was interested in. People have access to what’s happening online. It’s a broadcast that anyone can watch. These people are selling access to themselves. There’s a whole concept of “live my real life with me.” I thought there was more to that. That wasn’t all they’re putting out.

Is that why there’s an emphasis on nature and the details of small town life?

Austyn’s world was really cinematic to me. I filmed for a year before I found him. I thought “Here’s this kid living in rural Tennessee. He’s not around a ton of culture. He’s not really around anyone else with the same interests. He’s trying to make it.” For me, what nature represents in the film is that the human in him wants to be outside and in touch with people but he’s found this alternate world he’s escaped to. He feels comfortable and more accepted so he gets deeper and deeper down that hole. But it’s really human to retreat to nature.

How did you research the potential subjects and find Austyn?

I’m not in the world that these kids are in. At the beginning, I was going to a lot of the same channels the fangirls are going down, like getting in touch with them directly and sending them DMs. I realized it didn’t work and I was coming off as just another fangirl. Eventually, I realized I had to get on a tour. I knew that the meet-and-greets were where I was going to find a subject. The dynamic that goes on there is so complex to me. I had to figure out how to get myself on a meet-and-greet in order to figure out who was going to be the main character. We spent a year traveling around, filming various events and putting feelers out. Someone randomly found Austyn online. He had no following, but his personality was what we were looking for. He could represent a lot of people’s stories.

When he starts, he seems very sincere about this “Yo wassup bro, love and positivity!” persona that seems like a typical voice of a teenage YouTuber, but it seems like that forced positivity is something he’s trying to convince himself most of all to follow. Is that your sense as well?

The world that I entered is one of people trying to escape their situation. Something is wrong in their reality, so they’re seeking a new life in this online world, thinking “I want to be happy, I want to be positive, I want to feel good about my life because I don’t actually have these things in my life or feel that way about my life, so I’m going to enter a world that convinces me I can be that way.” You only look for this positivity culture if you feel like you need it. The interviews with these girls are so rich because they don’t naturally have that in their life.

It struck me that they’re finding solace in public discussions of addiction and self-harm, which were not really talked about openly when I was a teenager.

I think that it’s different if you’re a girl. You crave these mature relationships at a younger age, like between 13, 14, 15, 16. You start to feel emotions like a woman, but your actual maturity doesn’t match up to it. You have all these misplaced emotions, and you don’t know where they’re coming from. So a lot of young women turn that confusion inward. I experienced a lot of that and had friends that did as well. What connected me to this film was remembering being a teenage girl and struggling to feel love and connection. A lot of that self-harm comes from feeling like you can’t connect to other people and you aren’t loved, so you take it out on yourself.

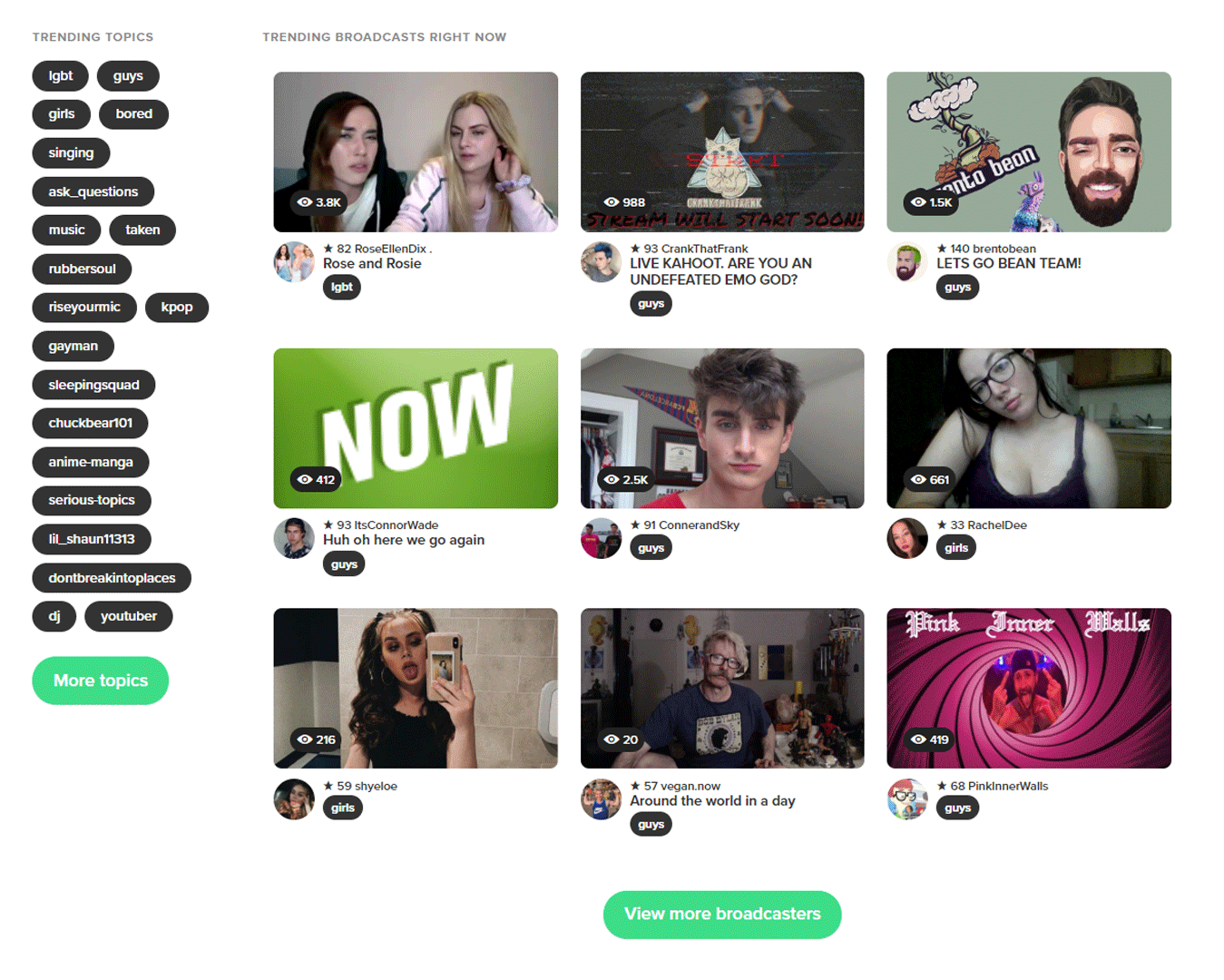

Screenshot showing recent broadcasts on streaming platform YouNow.

YouNow

I had never heard of the platform YouNow till I saw the film. It seems like technology and the platforms people use are speeding up faster and faster.

What’s really interesting is that now we’re a time when these apps are changing the way we think. When you’re someone who is raised on technology, like a lot of the kids in my film, it gets integrated into how you develop as an adult. I’m curious how this generation grows up with screens affecting their emotions. But to answer your question, all these apps have a moment where everyone rushes to them, and the moment passes. It doesn’t last forever or very long. It’s truly just a moment. Austyn’s story represents that too. The conclusion of Michael’s story shows that. They’re using this quick bit of fame to ride to the top. It parallels the fact that these apps don’t stick around. More and more things pop up. The culture’s about the masses. Everybody’s using this, so nobody’s using that anymore. You can’t have a culture around an app if there’s not an entire culture of people using it. The mentality is that they have to be popular to work, so each one becomes a popularity contest.

Justin Bieber seems to be the model for a lot of the boys in your film, but you can trace that kind of teen idol back to the Beatles. How do you see the fandom you depict fitting into a much larger history?

I think you’re right. Justin Bieber was one of the early models for how you can get discovered on the Internet, but now the market is saturated. Everyone has become their own channel, basically. We live in a time when everyone is their own brand in some capacity, whether you have a thousand followers or a million. I think that in terms of fandom, it is similar to older generations of teenage heartthrobs in that people are looking to them for inspiration and fall in love with them. What’s different in Jawline is that they’re selling their life. The commodity isn’t music or a performance. It’s “I, a person, am going to give you my affection. I’m going to care about you.” I think that’s really unique and created a new form of fandom.

How did your editorial process with Alex O’Finn go?

Alex is one of the best editors out there. I had a lot of ideas for the story, but he made them come to life. Alex knows how to tell a human story in a confident way. I never questioned him. For a documentary, having a good editor is everything. We cut it on [Adobe] Premiere.

You often do montages where we see the face of your subjects and hear sound from their interviews, but it’s not presented as a direct interview. What inspired that?

I was trying to figure out how to get inside people’s heads and express their fantasies and desires and what they’re dreaming about at that moment. I’m always experimenting with how documentary can show someone’s dreams. Most people have fantasy worlds that motivate them. I dream of being like this or that, and I put an element of fantasy into my films. Maybe for this film and earlier shorts, I’ve done that, but in the future I want to find other ways of showing what people are going through and not just telling the audience about it.

You’ve made shorts for outlets like Vogue, i-d and Dazed. Did they have different requirements than a feature film?

Absolutely. I’ve done so many shorts that by the time I started working on a feature, I felt really confident about the process of doing it from start to finish. A lot of the time when I’m making a short, I feel like I’ve got too much because I know I can’t include it. With a feature, I always want more. That was the main difference. I always wanted to make a feature and want to continue making features because I had so much to say with my shorts. It was always cut off. You can never finish a train of thought — you can only tell one little piece of it. It was very exciting to switch over to features because for the most part, I get to say everything I want to say. Then eventually, a feature starts to feel like you don’t have enough time!

“Fangirl” and “Fame” seem like rough drafts after seeing Jawline. They deal with the same themes and ideas.

When I have an idea for a feature, I also think “This could also be a great short.” Sometimes you feel like it does work as a short, sometimes you feel like you haven’t explored enough. If you’re going to work on a feature for so long, it’s about having an unanswered question. I think that when I found the live broadcast world, I don’t know if it’s good or bad. I don’t know why every girl shows up to the meet-and-greets or what they’re going through. I still have questions. I have to go with my gut that way. Does that topic hold my interest so that the more I delve into it, the more questions I have?

There’s a running theme of a fascination with youth in all of your films that I’ve seen. Do you have any projects planned which depart from that?

For me, creatively, I go through these obsessions. I get interested in an idea that can span over many projects and several years. Eventually, your life changes and you become interested in different things. The documentaries are very personal to me. I’m trying to work through my own emotions and certain things I’ve experienced. I’m trying to learn how people deal with certain situations and emotions. I just go with my interests at the time. For the past couple of years, I’ve been thinking about my time growing up and how different things are with technology as an extension of the self. But as a counter to that, youth culture is really interesting because it’s so visceral. There’s an arc built into it because you’re not going to be 16 forever. You’re going to look back on yourself as a stranger. I find it fascinating to capture that moment of time that’s so fleeting.

Jawline has a very tight narrative arc, with the tour Austyn goes on as a turning point. When you were filming it, was that apparent to you?

Absolutely not. I experience this with every single film I make, where in the moment I film something that I’m so sure is the scene I’m and the scene I showed up to get doesn’t happen for various reasons. We’re here, so we’re still going to film stuff. You wind up filming something that you don’t know what it’s going to be, and it’s the subject collaborating. You really have to surrender control in documentaries. You don’t know where everything goes until you play around with it in the edit. There were times when we thought this was going to be a rise to fame story. We went to go shoot and something was off with Austyn, and we didn’t know what was going on in that moment. You have to look back and reflect on the footage to see what’s happening. It’s never obvious in the moment, beyond knowing you have something interesting and good.

Do you see any parallels between your struggle to get your film made and promoted and Austyn’s hustle?

I think that it’s not with this film specifically. I relate to the obsession with showing people that you’re more than what’s apparent. The artist in me has something really big and urgent to say, but in filmmaking you have to convince so many people that it’s important. It can be really hard to do that. Austyn definitely experienced a form of that, where he felt that he could become somebody and change people’s lives if only he could get more views. In order to get your film made or even get any work in the film world, you have to have so much hustle in you. I wasn’t born into any connections. You have to find your way in. So in terms of how the entertainment world works, I definitely related to that.

I got the sense Michael was this nerdy kid who adopted this persona of a Hollywood player. Obviously, at the end we learn something quite dark about his behavior, but he seems much more enigmatic than Austyn.

That is what he puts forward. We were interested in the manager character. It was always a film about Austyn’s layers, but Michael was treated as a character. I never felt like I was hiding anything by doing so. That is how he acts, whether or not the camera’s rolling. I’m in awe of this young, hustling businessman who has tapped into a market that can only be navigated by someone of his age.

Has anything changed in Austyn’s life since the film was finished?

Austyn is caught up in school now. That’s a big one for him, because he messed up his school throughout the film. He still lives in Kingsport [TN]. He’s working at Starbucks.

Crafts: Shooting

Sections: Creativity

Topics: Q&A adobe austyn tester documentary documentary filmmaking liza mandelup premiere pro

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.