On In-Camera VFX, Building the Tesseract, and What a Black Hole Really Looks Like

On Sunday, Interstellar won the BAFTA award for best visual effects, an award presented — fittingly as it turned out — by Dr. Stephen Hawking.

Hawking’s longtime friend Dr. Kip Thorne, a renowned astrophysicist famous for his work on black holes and wormholes, was an executive producer on Interstellar, and worked with the team at Double Negative to create the scientifically accurate images in the film.

The BAFTA winners, who also have received Oscar nominations for best visual effects, include overall VFX supervisor Paul J. Franklin who helped found Double Negative in 1998; Andrew Lockley, visual effects supervisor at Double Negative, Ian Hunter, a co-founder of New Deal Studios, which provided miniatures for the film; and special effects supervisor Scott R. Fisher.

Written and directed by Chris Nolan, the Paramount Pictures production has five Oscar nominations in all. It received the AFI Movie of the Year award and has earned $664 million at the worldwide box office.

In Interstellar, a scientist named Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) leaves our galaxy by traveling through a wormhole to find an inhabitable planet for people on the dying earth. The exploration takes him onto planets with extreme weather, near a black hole, and, in the film’s climax, into a four-dimensional tesseract, a time-space continuum, to communicate across, well, time and space.

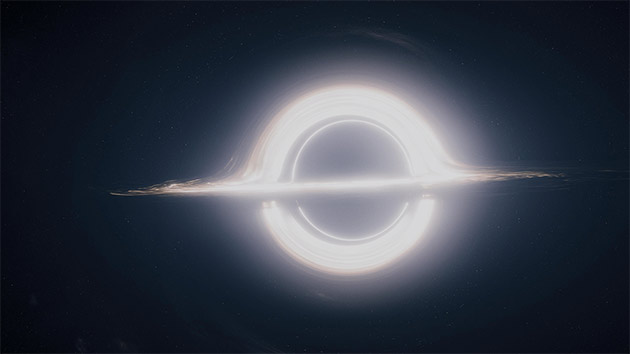

“The visuals alone are worth it,” writes film critic Christopher Orr in The Atlantic. The violent whirling of a dust-hurricane on Earth; the crash of a mile-high tidal wave on a distant world; the quiet, deep-space beauty of a black hole ringed by a glowing accretion disc.”

We spoke with Paul Franklin about the film, the fifth film on which he has collaborated with Nolan during the past 12 years. The collaboration has resulted in two BAFTA awards (Interstellar, Inception), five BAFTA nominations, one Oscar (Inception), and three Oscar nominations for best visual effects.

StudioDaily: Why do you think your peers voted last month for an Oscar nomination for Interstellar?

Paul J. Franklin: I hope they responded to the quality of the work and the way it supports the story. One thing that stands out is our use of physical miniatures, which is part of our philosophy to get as much as possible in front of the camera. Our original expectation was that we’d have more on the digital side for space travel, but in the end, 95 percent of the space shots used New Deal’s miniatures. If you’re going to make a science fiction film with space travel, miniatures are a great way to go.

The other thing that stands out is the work we did to create the black hole. We collaborated with Kip Thorne, our scientific adviser, who became an adviser throughout the film. Our philosophy for every aspect of the film was that it was all based on or inspired by scientific theory. Kip was our guardian of scientific truth. He would vet all the ideas in the script.

Did DNeg do all the digital visual effects?

Yes. As with Inception, Chris [Nolan] asked me to be overall supervisor. He was keen to keep all the work in one place. He likes to have one person directly responsible for the work to simplify the process. He brings DNeg departments inside the production itself. He says it’s like the past when visual effects artists worked for the production rather than independently. He likes that close collaboration. Inception worked out really well, so we’ve continued that since then.

How many visual effects shots were there?

We completed 700 digital post-produced finals for the film. Of those, 620 were fully IMAX, the rest anamorphic. We used a resolution of 5600 x 4000 lines. We also created in-camera visual effects work for another 150 shots. So, 850 shots. I think New Deal had about 150 shots with miniatures.

What do you mean by “in-camera visual effects?”

We used in-camera projection; we re-invented the front projection process. When you see something outside the spaceship, it was on stage. We created the images up front and projected them with digital projectors. The actors could see the images. We wrapped a big screen, 30 feet by 300 feet, around the main set of the Endurance [spacecraft], which we built on stage 30 at Sony in Culver City. It had windows on one side. We could project an image anywhere on the screen within reason. We also had two small spacecraft with wrap-around screens; three sets. The sets had more in common with flight simulators than greenscreen sets.

The people at DNeg in London created libraries of images, and rendered images of the black hole overnight, that we’d download first thing in the morning [in California]. The content creation process ran around the clock for about three months — Chris [Nolan] pushed me pretty hard to get the imagery. Andy [Lockley] and I had workstations on the stage and created new content during the day. We would adjust the images sometimes only moments before filming.

Our key reference was the video Commander Chris Hadfield made onboard the International Space Station to David Bowie’s "Space Oddity." He’s against the observation window and you see the Earth outside. It’s blown out. We wanted that look.

The company Background Images set up Barco projectors designed for live performances like rock concerts because they were robust enough to move around. We projected the images on an axis along the same line as the camera. We built a custom cage for the projectors and moved them with a forklift truck that had a 100-foot reach. Because we needed high luminance in the imagery to make it feel like available light photography, we converged two images to increase the exposure.

The guys from Background Images told me it usually takes two to three days to set up the projectors. I explained this to Chris. He said, “I’ll give you a maximum of 20 minutes between set-ups.” And they did it. We got between 150 and 170 shots that needed no additional post-production. And the actors had stuff to look at.

Tell us about creating the black hole imagery.

It was an eye opener. In the beginning of pre-production, we thought we’d look at scientific ideas, talk to Kip, make concept paintings, and the visual effects crew would make images. Instead we approached it from the viewpoint of how could we put physics and math into it and make it real.

The gravity of the black hole is so intense it warps the space around it so a light ray passing through this region of space gets bent. The physics for how it warps space is well understood because Kip and Stephen Hawking worked it out in the 60’s and 70’s.

Kip gave us formulaic versions of Einstein’s equation to produce light traveling around the black hole. Our simulation of the black hole revealed extraordinary detail that Kip tells us has never been seen before. No one has needed to do this before – to fly a spacecraft toward a black hole. Scientists had been doing very specific simulations of limited aspect. The demands of the story gave us a different viewpoint, and we revealed things in the light travelling past the gravitational lens around a black hole that had never been seen before.

Obviously, it’s a visual effect. We designed colors and exposure. But what we see is what physics tells us we should. Kip worked with our team to implement a renderer that met the demands of IMAX images. It took a long time to create that gravitational renderer, the DNGR, and we continued refining it.

What does DNGR stand for?

Double Negative General Relativity. We’re about to publish a paper with Kip Thorne for the Journal of Classical and Quantum Gravity. [“Gravitational Lensing by Spinning Black Holes in Astrophysics, and in the movie Interstellar” by Oliver James, Eugénie von Tunzelmann, Paul Franklin and Kip Thorne; provisionally scheduled for February 2015. See a sample at DNeg's website.]

What is the idea behind the tesseract in Murph’s bedroom?

Chris Nolan said we needed to create a space where Cooper could navigate up and down the timelines of history and find specific moments of time. A brilliant concept. But we didn’t know what that looked like. We spent months of research and experimentation with the visual effects team. It’s the embodiment of the theory that every piece of matter in the universe leaves a trail of matter behind it in time. It comes from the idea of the world line in physics. The tesseract is a visualization of all the world lines, all the objects in Murph’s bedroom in an infinite lattice. Where they intersect there is a 3D image. Each of these separate versions of the room represents successive moments in time. Cooper could insert a message into the past by pushing on the world lines. When we showed this to Chris, he said it would be really great if we could build it partly as a physical set, so that added a level of challenge.

How did you create the tesseract?

When you look at the sequence, you see rooms connected by timelines. We built one section of the tesseract approximately 60 by 100 feet long by 60 feet high. If you look one way, you see the bookshelf. The other way is a wall with a window. The timelines were extruded objects – objects in the room stretched out into long tubes. The books streaming up and down from the shelves were a solid object.

By the time they shot the tesseract, we were confident of the projection process. We carefully lined up 16 projectors that ran simultaneously to project onto one part of the physical set. When Cooper looks out the window he sees horizontal trails, blurs of texture. We created those images and projected them on set. We also wanted to show information along the world lines that connect different moments, to show stuff moving along these things like film strips in and out of the room. We built the timelines out of wood, medium-density fibreboard and plaster. They had a surface color and CG textures pasted onto them. We gave the art department images that we’d created and printed to make streaked timelines. Then we projected animated images on top of these long thin surfaces. We also projected images onto the bookshelf wall, too, but mostly just onto the timelines.

Matthew [McConaughey] was on a wire rig floating around in front of the projectors. The grips did a brilliant job moving him off the images. Obviously, we had to paint out his wire rig later.

We didn’t do the complete tesseract with projections, only part of the set. But it gave us the basis in photographic reality. There were moments that were entirely CG, but it all takes its lead from photography.

Any other visual effects you want to highlight?

The ocean wave. I had an amazing level of control that allowed me to design and create specific forms, to create 4000-foot waves in specific ways, yet that looked compellingly real. We hit a sweet spot in animation techniques and have a detailed, amazing simulation of a water surface that swept the spacecraft away.

What did you learn from working on this film?

With the right people and the right approach, you can make extraordinary things. I’ve always felt there was no limit to the imagery we can create. This film refined my approach to making visual effects, which is always to think about what is the value of the image, what is the story you’re trying to tell, and then to find a way to make the image.

With front projection, it was possible to design the visual effect simultaneously with the production of the film rather than pushing it off into post-production. It’s virtual production that doesn’t ignore what we’ve learned over the past 100 years of filmmaking, all that physical reality developed over the last century. We brought the visual effects world, which has developed separately from the physical, onto the set and had it be part of the filmmaking process. By bringing visual effects forward during the production cycle, the creative collaboration has a direct impact on the film. And we made design decisions by what was shot on the set, so it was one completely integrated whole.

Does the film push the state of the art of visual effects?

Every year what impresses me most is not the advances in technology, it’s the advancements in technique. The skills of the artists get better and better every year. When you look at the work in Interstellar, the integrity of compositing, the design of shots — everything has gone much further than in the past.

In terms of technology, DNGR is a major achievement to visualize black holes and wormholes in extraordinary detail and produce something visually compelling.

At the premiere of the film in London, Kip Thorne brought Stephen Hawking along as his date, so we all got to meet him. That typifies the relationship between art and science, which is at the heart of the visual effects work on Interstellar.

Tell us about the other nominees.

Andrew Lockley is one of my longest standing collaborators. He was a compositor on my first credit. My background is 3D CG. He brings a fantastic in-depth understanding of compositing.

Ian Hunter, who was in charge of our miniatures, has been working with Chris Nolan since The Dark Knight, and our relationship goes back to The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and before that, to DNeg’s first project in 1998, Pitch Black. And of course Ian has a regular team we’ve been working with for 15 years.

Scott Fisher, our special effects supervisor, is another long-standing member of the Chris Nolan team. He was on Dark Knight Rises and Inception. He brought a fantastic in-depth understanding of mechanical engineering to the big gimbaled sets and the two robots. The robots were, for the most part, cleverly engineered physical devices puppeteered by Bill Irwin. The dialog between Matthew and TARS [the robot] was adlibbed and recorded on set; production sound. It wouldn’t have happened without TARS on set. We only used a bit of CG when the robot turns into a pinwheel and splashes through the water.

It’s interesting that the same group has worked together on many Chris Nolan films.

It’s my fifth film with Chris Nolan [and] my 12th year working with him. It’s the defining creative relationship of my career. He is the most extraordinarily surprising individual. He’s constantly thinking of new ideas. Chris pushes us, never lets us rest on our laurels, never lets us get away with unsupported assumptions.

Do you have another Nolan film in your future?

I have no idea. He never shares that with us. When we finished The Dark Knight Rises [in 2012], Chris mentioned that he was thinking about a new film. The farthest thing from my mind was black holes and visualizing time.

Right now, I’m helping out on some other DNeg shows. I was away from home for over a year making Interstellar.

Gravitational Lensing by Spinning Black Holes in Astrophysics, and in the Movie Interstellar

More Oscar-nominated VFX Supervisors:

Stephane Ceretti on Guardians of the Galaxy

Dan Lemmon on Dawn of the Planet of the Apes

Dan DeLeeuw on Captain America: The Winter Soldier

Tim Crosbie on X-Men: Days of Future Past

Crafts: VFX/Animation

Sections: Creativity

Topics: Project/Case study Q&A oscars 2015 oscars 2015 vfx supervisors paul franklin VFX

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.

Leave a Reply