Three Big Innovations, the Current State of Storytelling, and the Problem with VR

Dr. Ed Catmull co-founded Pixar Animation Studios in 1986 with Alvy Ray Smith, Steve Jobs, and John Lasseter, and it has become one of the world’s most successful studios. He is currently President of Pixar and Walt Disney Animation Studios. Catmull is a pioneer in computer graphics. He led teams of artists and CG pioneers prior to founding Pixar, and is still doing so at Pixar. Among his honors are four sci-tech Academy Awards: two Technical Achievement Awards for the original concept of subdivision surfaces and for significant advancement in rendering exemplified in RenderMan, and two Scientific and Engineering Awards for pioneering innovations in digital image processing and for the development of RenderMan.

Pixar’s many achievements need no iteration beyond a brief mention that eight of the studio’s 16 feature films have received Oscars for Best Animated Feature, with Up and Toy Story 3 also nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture. All told, Wikipedia counts 210 awards won and an additional 211 award nominations for Pixar’s 16 feature films.

Catmull received the Academy’s Gordon E. Sawyer Award in 2009, the IEEE’s John von Neumann Medal in 2006, the Annie Awards’ Ub Iwerks Award for Technical Achievement in 2005, the PGA’s Vanguard Award in 2002, and the VES Georges Méliès Award in 2005. He is a VES fellow and a Computer History Museum fellow. Catmull’s 2014 book, Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration, written with Amy Wallace, was named one of the best books of the year by The Huffington Post, the Financial Times, Success, Inc., and the Library Journal.

We spoke with Ed Catmull about changes in technology between Finding Nemo (2003) and Finding Dory.

Ed Catmull. Photo: Deborah Coleman/Pixar

Can you point to a particularly important technical innovation that happened between Finding Nemo and Finding Dory?

I want to put that in context. Unlike technology in the early days of filmmaking, where technical changes happened sporadically, in this era what we have is continual change. There might be small changes. There might be big steps.

Thirteen years ago, our humans were not very realistic. They looked good in The Incredibles, of course, but a few things were not up to a high level. “OK,” we thought, “We’ll get better.” And, we did. During this time we completely rewrote our animation system, which had gotten up to version 19. The new system, Presto, was a 100 percent rewrite to put the animation system on a modern foundation for future growth. It took eight years of development, with a lot of trial and error. Everyone said, “Boy was that painful. Make sure we keep doing that,” and “There’s blood on the floor. I’m so glad we did it.” I love that attitude.

One thing we’ve tried to do relentlessly though our history is to have change and take risks. If we try something and it doesn’t work, we gain insight. The trick for both the people working on films and the research people is to continuously try something new and try something hard.

All images from Finding Dory © Disney • Pixar

Did you introduce any changes with Finding Dory?

We introduced three big things and there were risks with each one. We called the combination RUKUS. It was called “total pipeline annihilation,” and it many had concerns, but at the same time, we said, “Let’s do it. Let’s make this happen.”

The three things were …?

The architecture of RenderMan was completely re-engineered. This was the biggest change in 25 years, but it moved us forward with realistic light simulation and user interactivity. It is particularly suited to complex lighting problems like water and glass.

The second was something that is still in development, which was moving to [The Foundry’s lighting and look-dev technology] Katana. It changed the way we did real-time and multi-shot lighting.

The third was that we changed the pipeline underneath with USD, Universal Scene Description. That’s being open-sourced to the rest of the industry. [See graphics.pixar.com/usd/]

Why are you open-sourcing USD?

Disney, ILM, and Pixar have open-sourced a number of things. I believe strongly in participating in a wider community. Secrets are less important than having a healthy industry.

We’re not a big industry. We have very high visibility because of what’s made, but there aren’t that many companies. That’s one reason we have always published. For the last few years there have been more papers from the Disney companies than any other place because we believe in sharing.

In computer animation studios, as you know, everything is visual effects, but these studios have a long time horizon. By contrast, the visual effects houses, which have slim margins, are driven to make rapid changes because of their continued existential threat. So, we have this really interesting dynamic of two different timeframes, which drives the industry forward.

What technical changes do you foresee?

If you look at what it will be like in five or 10 years, we have pretty good visibility on that. We are deciding on that technology now. Lighting still needs to be fully real-time. The full integration and controllability of simulation is a major challenge. Five or 10 years from now, when chips and graphics boards are even faster, that will have a major implication on simulation, on control of complexity, and on reducing the size of a team so everyone feels more ownership in an entire film. Obviously one consequence now of new, faster chips is that people are all abuzz about virtual reality. So it’s not a single thing.

In the last 20 years, we have had continuous change, more than at any other time in the history of the film industry. Initially, there was a step function: the first CG film, Toy Story. Around this time visual effects had a major impact on filmmaking. These initiated a process of incremental changes, some bigger than others. But even a big step is a result of previous incremental changes that most people aren’t aware of. Global illumination was a big step, but it started with people experimenting in universities, then people began to integrate it into visual effects pipelines, and finally incorporating it into products, benefitting all.

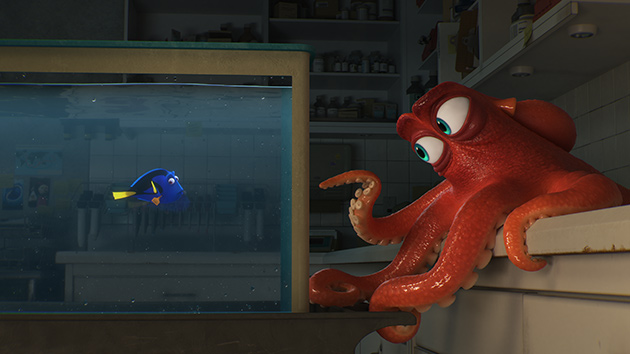

So what’s the viewpoint to take? From the outside, if you look at the octopus in Finding Dory, you might think you’ve never seen anything like that. And the look of the film is quite different from Toy Story. Those look like big steps. But from our side, it’s about how we manage the incremental changes and push and drive them and keep that alive as a mindset going off into the future. It’s not like we will reach a point where we will run out of things. If you look at it as managing change by introducing new capabilities all the time, it means a continual evolution.

What’s your take on virtual reality?

As you know very well, it’s been around for 30 years. The only thing that changed was that they got rid of the lag time, which led to a perceptual difference in what we experienced. It didn’t change the other problems, but it made it possible to think about new possibilities. I don’t know what all of the uses are, but I have a rough idea.

At Disney, we have six R&D centers: ILM, Disney Animation, Pixar, Imagineering, and the two research centers at CMU and Zurich. Each are using the new, faster graphics boards for VR. We want them all to take different approaches. Our view is that the technology used in each studio is decided by that studio. No one tells them that they must use “best practices.” So that means there are no losers, and if there are no losers, we’re all willing to share ideas. We want different mindsets.

When you look at the full scope — at shared experiences, games, explorations of worlds, new stories and as VR as a tool in industries beyond ours — I find that exciting. But storytelling in VR, that’s a hard problem. I’m not skeptical about VR in gaming, theme park experience, shared experiences across the internet, in layout and design for animation, and in AR. But I am skeptical about theatrical storytelling in VR.

Why are you skeptical about theatrical storytelling in VR?

One reason. Theatrical storytelling does not take place in real time, and almost no one realizes this. Good editors know they’re messing with time. Someone starts walking across a room, you cut, and he’s at the door, and the audience never notices. You can do that in film. VR is different. So I’m expressing this skepticism. But we just funded research groups at these R&D centers, and the people there think I’m missing something. If they prove me wrong, that’s awesome. I never mind being proven wrong. And the truth is, if they can’t tell stories, they’ll come up with something else. We can’t lose.

Incidentally, throughout my career there have been several times that I was skeptical of the approach that some suggested, but I wanted them to prove I was wrong. When I was doing my original rendering research and animation research at [the University of] Utah, [professor and computer graphics pioneer] Ivan Sutherland said, “I think this isn’t going to work.” He was an extremely smart mentor, who was skeptical. I viewed his objections as problems I needed to solve. Here’s a problem. Let’s go solve it.

What problems are you looking at solving today?

We have a non-technical problem. Our films are very expensive to make. The methods of distribution and revenue collecting are changing. On the business side, there are a number of things in terms of how you make money. We are a commercial business. We want to make art, but we want to make money. Everyone understands that. When you spend a lot of money making these films, you’re at greater risk. So if we can adopt technology in a smart way, we can lower the risk. We want to do that because we have a lot of stories to tell. If we can lower the costs, we can take bigger artistic risks.

At Pixar, we’ve always felt safe about taking big risks. Up and Ratatouille were big risks. Those films in particular do not pass the elevator test. They were not cheaper to make, and we were willing to do that. But we would rather be in a place where we could try things that are riskier or try things for smaller markets. We keep that integrated into the culture, keep pushing, and staying open for possibilities.

The VR experiments are about trying something new. We don’t know what they might open up.

That’s what I think is exciting about special effects and animation. It’s filled with people who want to try something new, to prove something. That’s been true from the beginning. We proved it’s possible. Everything is about how you push change. Change is going to happen, so are we the ones that will push it? How do you make it safe to try things that are new? We want to be encouraging. We never want to be those people we fought against.

You talk about continual change, but has anything stayed the same?

Stories. If you look at the stories, the taste in stories, the pacing, and some fundamental things are different. Even though many older films are considered to be classics, the pacing wouldn’t hold up today. But what hasn’t changed is that the way we communicate with others is through stories. It’s what we emotionally connect with. Mythology, metaphors, kids on our laps, chatting with people — stories have been important throughout history. We’re participating in a long legacy of telling stories to each other. The pacing might change. But the fact that we do it will not change.

Crafts: VFX/Animation

Sections: Technology

Topics: Animation ed catmull katana Pixar siggraph 2016 The Foundry

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.

Leave a Reply