Imageworks Creates Digital Make-up for Tom Cruise and Adds Period Details to WWII Drama

“The biggest and most delicate work we did was on Tom Cruise,” Hoover says. “Bryan’s intention was that when you watch the movie, [Stauffenberg’s] injuries become part of him and you accept it. The visual effects in this film weren’t about spectacle. They were about taste, subtlety, and support for the character.”

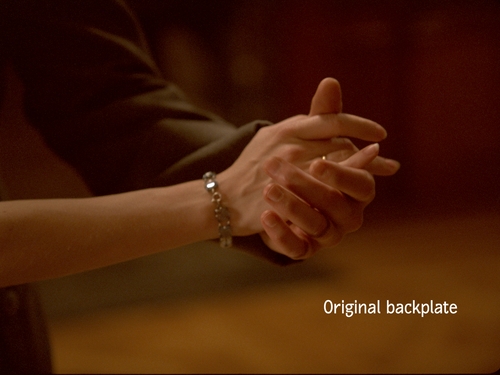

Hand-Eye Coordination

To remove Cruise’s pinkie and ring fingers on his left hand, the artists started by scanning the cast used by the prosthetic makeup artists to create the stump for his right arm. “We didn’t scan Tom Cruise’s hand because of time considerations,” Hoover says. “It was easier to scan the cast.” Using that scan and photographs of Cruise’s hand as reference for size and scale, modelers working in Autodesk Maya sculpted the digital duplicate. The photographs also provided material and reference for texture artists.

Tracking artists working with Hammerhead’s rastrack and 2d3’s boujou matched the digital model to Cruise’s hand frame by frame in the edited footage. “Interpreting the movement of the hand became a particular kind of skill,” Hoover says. “I learned a lot about the intricacies of 3D tracking because many of the shots are close-ups.”

For example: “If you’re looking at the hand from the camera’s point of view, you can position the 3D model to look like it matches on one frame,” he says, “but when you load it into Maya and move the camera around, you find that the rig is broken. You’ve positioned the fingers in a way that isn’t humanly possible.”

Moreover, unless the trackers considered isometric and other points of view, the shadows wouldn’t be in the right place to blend correctly into the photography when the lighters added the key lights. “We might have gotten away with more if we had replaced the whole hand with the CG hand, but I wanted to keep as much of Tom’s hand as possible,” Hoover says.

Thus, even though the crew lit and rendered the entire digital hand (in Pixar’s RenderMan) doing the same movements as Cruise’s hand, they used as little of the digital hand as they could. Usually, that meant little more than the digital stubs for the missing fingers, although sometimes they needed to reconstruct areas of Cruise’s palm that his fingers had covered. Similarly, the artists filled in background areas that the fingers had covered before the digital surgery.

Compositors also rebuilt backgrounds behind Cruise’s right hand after its digital removal from his coat sleeve. “The stump is often inside [Stauffenberg’s] sleeve,” Hoover says. “That’s something Brian spent a lot of times considering ‘ when you saw the stump and how much of it you saw. It can be disturbing and sometimes we didn’t want the distraction from the story lines and emotion. Other times we used it to make a scene more disturbing. We had documentation that said Stauffenberg didn’t hide his injuries.

Cruise wore a prosthetic stump in a few shots, it but because it lengthened his arm. the stump is usually digital. Sometimes, compositors working in Inferno inserted a digital photograph of the prosthetic, but more often, they added a digital representation of the prosthetic. “It was easier to animate Tom’s movements accurately in the 3D world than to try to track in a photograph,” Hoover says.

The crew didn’t have to track in an artificial eye, though. Through much of the film, Cruise wore an eye patch and when he took the patch off, he wore a glass eye. “[The artificial eye] was much bigger than a contact lens,” Hoover says. “It couldn’t have been comfortable.” When Cruise moved his eye, the glass eye moved, too, as it might have for Stauffenberg.

“That’s how it was at the time,” Hoover says. “The manufacturer of Stauffenberg glass eye still exists and they had documentation. But sometimes in the film, it looks too realistic, so we moved it not quite right to make the idea that his eye is missing more dramatic. It’s very subtle.” The crew also fiddled with the color to make the whites a little whiter to give it a slightly unreal feel.

Reconstructing the Sets

Valkyrie takes place in 1943, and although some facilities built at the time still exist, Imageworks needed to add others and remove modern elements to create the historically accurate wartime environment. “It was a mixed bag of tricks,” Hoover says. “We painted in some environments, painted out others, and blended fully rendered 3D models into photography.”

Hoover took HDRI images of each set to help lighters match the footage and surveyed the areas using a system from Trimble designed for architecture and engineering. “[The Trimble system] sits on a tripod and will do a 360-degree scan of a room using a laser for measurement to 150 meters,” Hoover says. “Then it puts together a point cloud and can apply photos to the dots. When we bring a point cloud into the computer, we see a photographic representation, which helps us understand what and where the points are.”

Hoover used the Trimble system to scan sets, buildings, and airplanes, usually during lunch break. “We could tell the system to scan based on how much time we had, and it figured out the resolution. So, when we knew we had, say, 45 minutes for lunch, we’d set it for 45 minutes and it would get as many points as possible.” On the other hand, if Imageworks planned to create a digital model from the scan, the crew would remove the time constraints and set the system to scan at as high a resolution as possible to get a dense point cloud.

“It was a very valuable tool and I’d like to use it again,” Hoover says. “The only problem is that the software is set up for architectural applications, so the way the points are ordered is not in a normal x-y-z path in columns in a text file. It took a little software manipulation to make the data usable in Maya.”

Rebuilding Berghof

One of the crew’s largest construction jobs was to recreate Hitler’s Berghof retreat, a building in the Bavarian Alps near the Austrian border south of Salzberg. None of the original architecture remains, and the area around it now has a golf course.

Location scouts found a nearby Austrian ski resort on a mountain that resembled the Berghof location. Imageworks removed a chateau and all the skiing paraphernalia and photographed the mountain. Because the chateau was taller than the Berghof, the crew had to rebuild the top of the mountain and the mountains in the background that it had blocked.

The shot of Berghof starts from a couple miles away and ends within 100 feet of the building, which meant Imageworks needed to provide a huge amount of detail. “Hitler had bought Berghof as a small retreat, but by 1943, it was a large building with a gigantic picture window in the living room that moved down into the floor below to open the room to the outside,” Hoover says. “We built a fully digital version of his retreat and put CG cars and CG soldiers on the outside.” The interior, though, was a set with no ceiling and green screen for the window.

Before building the retreat, Imageworks consulted vast amounts of research material, as they did throughout the process for each sequence. “We have terabytes of historical information for this film,” Hoover says. “For Berghof, we had hundreds of photographs and short films of Hitler entertaining his officers there. And we got the actual plans of the Berghof. We followed the plans exactly – literally extruded the blueprints.”

For textures, the crew photographed the front steps and a small portion of the walls that the art department built, altering the images as needed to make the building look authentic.

Making authentic planes required less research ‘ they had real WWII airplanes to work with. “We had two vintage restored Junkers, the aircraft Hitler flew in, and two working Messerschmitts,” Hoover says. “We shot them from helicopters using a stabilized camera rig.” When Singer wanted more planes, Imageworks cut planes from one shot, pasted them into another, and re-tracked and re-animated the images.

Similarly, for the North African attack on Stauffenberg, pilots flew two real P40s over the set, but to create specific choreography in some shots, Hoover used CG replicas of the P40s.

“At one point we thought we should use Spitfires because the P40s were American and the British were in Africa, but we had historical information that pointed us to the P40s,” Hoover says.

This attention to historical detail peppered the entire process – sometimes to an extreme. The crew that mowed the grass to re-create a runway on an old World War II battlefield, for example, had to be careful not to step into the nearby forest, which still contained unexploded Russian bombs.

“It was fascinating to be able to film a version of what happened in the places where the events occurred with soldiers in real uniforms and real vehicles,” Hoover says. “It was about as real as you could get and not be there. My mantra was that people should see the movie and not have any sense walking away that there were any effects at all. I hope that when people leave the theater, they think what they saw was authentic.”

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.

The special effects were so realistic, I had to find out what happened to Tom Cruise’s hand!